Kamala Harris and her running mate Tim Walz made their political debut to throngs of screaming supporters in Philadelphia on Tuesday night. The next day, they hopscotched over to Eau Claire, Wisconsin, for a casual meet up with 12,000 Bon Iver-heads, before touching down in Detroit, where some 15,000 people turned up on the Detroit Metro tarmac to greet them.

Harris was on stage inside an airplane hangar a little while later, when her speech — and the positive vibes that have propelled her campaign for the past two and half weeks — were interrupted by protesters demonstrating against the Biden administration’s decision to continue arms shipments to Israel, even as that country’s right-wing government uses those weapons with little regard for the lives of civilians, aid workers, and journalists. An estimated 40,000 people have been killed in Gaza since the war began in October.

“Kamala, Kamala, you can’t hide. We won’t vote for genocide,” the protesters chanted.

Delivered in Michigan — where 100,000 people withheld their votes for President Joe Biden in February’s Democratic primary over his administration’s Gaza policy — the message has some teeth. Hillary Clinton lost the Democratic stronghold by just 10,704 votes in 2016; Biden reclaimed it for Democrats in 2020, but with a slim, 154,000 vote-margin.

Harris seemed, initially, to take the interruption in stride. “I’m here because we believe in democracy. Everyone’s voice matters, but I am speaking now,” she said after the first chant broke out. Then, she resumed her speech: “Look, if he is elected, Donald Trump intends to give tax breaks to billionaires and big corporations, he intends to cut Social Security and and Medicare, he intends to surrender our fight against the climate crisis and he intends to end the Affordable Care Act — ” The chanting continued, and Harris’ patience, seemingly, ran out. “You know what? If you want Donald Trump to win, then say that. Otherwise, I’m speaking,” she said.

The moment was clipped and quickly spread around social media, where it was received poorly by would-be Harris supporters hopeful that a change at the top of the Democratic ticket would also portend a meaningful change in U.S. policy as it relates to Gaza.

There have been subtle signals that Harris would be more inclined than Biden to support such a change, including her calls for a ceasefire that pre-dated Biden’s, reports she’s advocated for stronger public criticism of Israel’s refusal to let humanitarian aid into Gaza, her personal outreach to a man who lost dozens of family members in the war, and her selection of Walz as a running mate.

But in the absence of Harris herself articulating a policy vision distinct from the current administration’s, the viral moment seemed to confirm the worst fears of voters who are disturbed by the fact that U.S taxpayers are funding what United Nations experts have assessed can reasonably be called “a genocide.”

Before they took the stage on Wednesday, Harris and Walz were introduced to the founders of the Uncommitted Movement, Layla Elabed and Abbas Alawieh, who say the campaign invited them to Wednesday’s rally. The invitation, extended after months of lobbying for both a meeting to discuss an arms embargo and speaking slot at the convention, was for a brief introduction during a photo line.

“It was only a few minutes in the photo line-up, and I did get really emotional,” Elabed tells Rolling Stone. “Harris was incredibly sympathetic. And I could feel her sympathy was very genuine… And when I said, ‘Will you meet us?’ She said: ‘Yes, let’s meet.’” Elabed and Alawieh say Harris then directed a staffer to arrange a meeting with them. They’re hopeful it will take place, but no date has been set.

“Obviously we need more than just sympathy… We can’t eat sympathy,” Elabed says. “Palestinians, who are taking the forefront of this assault, can’t live off of sympathy. We need a real policy shift. We need a real change.”

After the event, the Uncommitted Movement sent out a press release declaring that Harris had agreed to meet with them to discuss an arms embargo. The vice president’s national security advisor, Phil Gordon, immediately disputed the idea that she would support one. A spokesperson for the campaign, meanwhile, said only that Harris “affirmed that her campaign will continue to engage with those communities.”

Alawieh and Elabed remain optimistic about the prospect. “It feels like the Vice President is interested in engaging,” says Alawieh, who worked with members of Harris’ team as a legislative director in Congress. “I know Vice President Harris’s team is a strong group of people, many of whom are in touch with Arab American, Muslim American, and Palestinian American community leaders, so it hasn’t surprised me that there’s been more responsiveness, certainly, than what we were getting from President Biden.”

He added that they recognized that Harris’ campaign is new and that she and her staff are still working to get it off the ground. At the same time, he says, the Democratic campaign reset presents “a real opportunity to turn a new page on Gaza policy.”

“My sense is that the last 10 months of this administration’s Gaza policy have been disastrous, and that as we go into the most important months of this campaign cycle, a hypocritical campaign stance that says ‘Cease-fire’ in one in one breath, and then continues to support the unconditional flow of weapons in the in the next is not a sensible policy, and it’s not a good campaign strategy,” Alawieh says. “Democratic voters, including over 100,000 here in Michigan, have self identified saying that Gaza is a top policy issue for them. So if you’re listening to voters, you need to have an update to this policy. And I’m hopeful that her team sees that.”

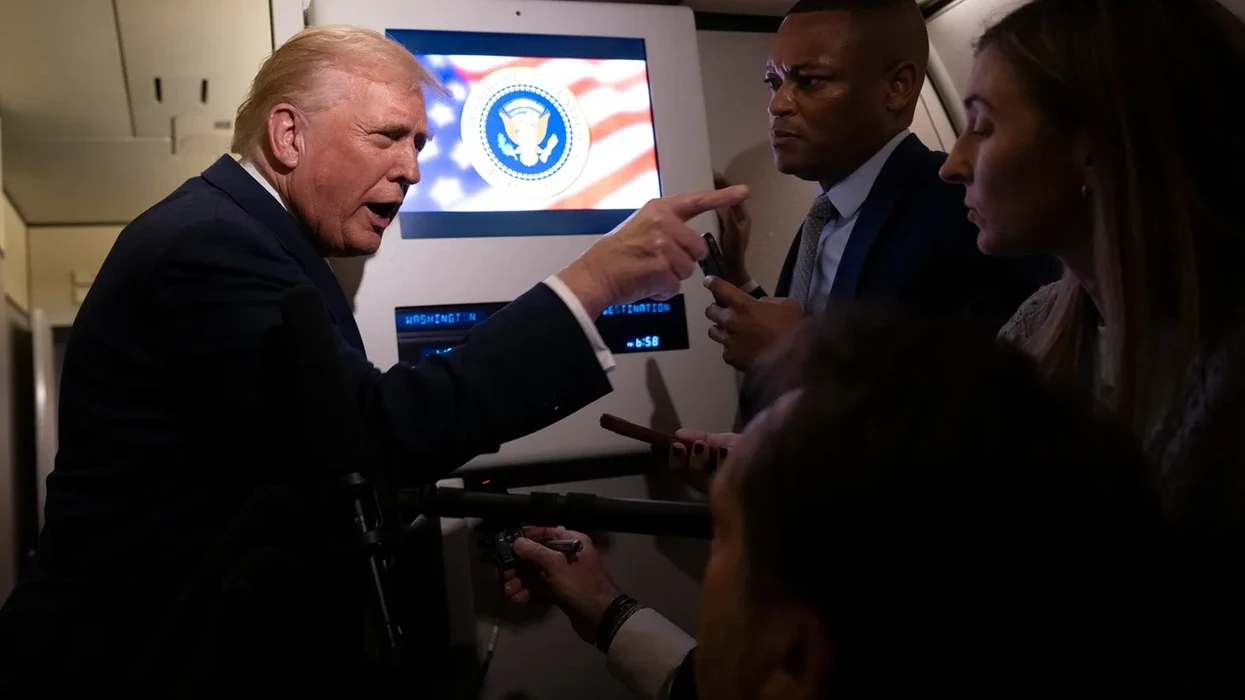

President Donald Trump discussing Venezuela at a press conference at Mar-a-Lago.

Why Venezuela Could Be a Turning Point in Gen Z’s Support for Trump

When Donald Trump called himself “the peace president” during his 2024 campaign, it was not just a slogan that my fellow Gen Z men and I took seriously, but also a promise we took personally. For a generation raised in the shadow of endless wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, it felt reassuring. It told us there was a new Republican Party that had learned from its failures and wouldn’t ask our generation to fight another war for regime change. That belief stood strong until the U.S. overthrew Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro.

Growing up in the long wake of the wars in Iraq in Afghanistan shaped how my generation learned to see Republicans. For us, “traditional” Republican foreign policy became synonymous with unnecessary conflicts that caused young people to bear the consequences. We heard how Iraq was sold to the public as a necessary war to destroy weapons of mass destruction, only to become a long conflict that defined the early adulthood of many millennials. Many of us grew up watching older siblings come home from deployments changed, and hearing teachers and coaches talk about friends who never fully came back. By the time we were old enough to pay attention, distrust of Bush-era Republicans wasn’t ideological, it was inherited from what we had heard.

As the 2024 election was rolling around, that dynamic had flipped. After watching wars in Ukraine and Gaza dominate headlines while Joe Biden was president, the Democrats were now the warmongers. My friends constantly told me how a vote for Kamala Harris was a vote to go to war. On the other hand, Donald Trump and the Republicans were the ones my friends thought could keep us safe. “I’m not voting for Trump because I love him,” one friend told me. “I’m voting for him because he cares about us and I don’t want to go fight in a stupid war.” For many of my friends, much of their vote came down to one question: Who was less likely to send us to fight? The answer to them was pretty clear.

Fast forward to now, and Venezuela has begun to complicate that belief. Even without talk of a draft or a formal declaration of war, the renewed focus on U.S. involvement and troops on the ground has brought back the same language of escalation my generation was taught to distrust. Young men online have been voicing the same worries, concerned that the ousting of Maduro mirrors the early stages of wars they were raised to fear. When I asked a friend what he thought about Venezuela, he shared that same sentiment. “This is how all these wars always start,” he told me. “They might try to make it sound like it’s not actually a war, but people our age always end up being the ones that pay the price for it.” For young men who supported Trump because they believed he represented a break from interventionist politics, Venezuela blurs the line between the “new” Republican Party they thought they were backing and the old one they were raised to reject.

For many young men, Venezuela has become a major part of a broader shift of how they view Trump. A recent poll from Speaking with American Men (SAM) found that Trump’s approval rating has fallen 10 percent among young men, with only 27 percent agreeing with the statement that Trump is “delivering for you”.

Gen Z men’s support of Trump was never about ideology or party loyalty, it was about the idea that he had their back and would fight for them. But that’s no longer the case. Recently, Trump proposed adding $500 billion to the military budget. Ideas like that will only hurt the president with young men. My friends don’t want more military spending that could get us entangled in foreign wars; they want a president who keeps them home and fights for their economic and social needs. As Trump pushes for a bigger military and more intervention abroad, the promise that once made him feel like a protector of young men now feels out of reach.

For my generation, Venezuela isn’t just another foreign policy dispute, it’s a conflict many young men worry they could be the ones sent to fight. Gen Z men didn’t support Trump because he was a Republican, but because they believed he was different from the old Republicans. He would be a president who would have their back, fight for their interests and keep them from fighting unnecessary wars. Now, that promise feels fragile, and the fear of being the ones asked to face the consequences has returned. For a generation raised on the effects of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, the idea of another war isn’t abstract, it’s personal.