Supreme Court puppetmaster Leonard Leo has long been invested in the election of Republican attorneys general, who are well-positioned to challenge regulations and bring precedent-setting cases before his friends on the high court. Leo and his dark money network have taken a keen interest in the GOP primary for attorney general in Missouri, pouring millions into the race to replace a conservative appointee with a lawyer who calls Leo a mentor.

Leo’s favored candidate, Will Scharf, has served as former President Donald Trump’s lawyer, including in the presidential immunity case at the Supreme Court. The court ruled that the former president is entitled to immunity from prosecution for official acts committed as president, complicating and further delaying his criminal cases — while giving the executive a powerful shield to do crimes.

As Trump’s judicial adviser, Leo helped him select three Supreme Court justices and build a 6-3 conservative supermajority. Scharf, meanwhile, has worked for Leo’s network, his consulting firm, and in the Trump Justice Department. He worked to help confirm two of the Trump-Leo justices — Brett Kavanaugh and Amy Coney Barrett.

The New York Times reported last fall that Trump and Leo, who received a historic $1.6 billion donation to supercharge his conservative dark money network, were on the outs. You wouldn’t suspect that watching the pro-Scharf advertising Leo is funding paint Trump as an unfairly targeted hero — and lionize Scharf for representing him.

“When prosecutors lie, when judges put politics over justice, when the whole legal system is gunning for you, you need one heck of an attorney,” says an ad for the group Leo is funding. “You need Missouri’s own Will Scharf. President Trump relies on Will Scharf as one of his lawyers to defend him from legal persecution and election interference. Will Scharf is taking on the entire legal and media establishment to defend President Trump.”

The ad says succinctly, “Will Scharf: Trump’s attorney.”

A second ad from Defend Missouri says that Republican Attorney General Andrew Bailey “went easy on a violent career felon,” who went on to “shoot two cops.” The Missouri Fraternal Order of Police called on Defend Missouri — a state Super PAC affiliated with the Washington-based Club for Growth — to take down the ad.

Leo and his Concord Fund have donated $7.4 million to Defend Missouri and the Club for Growth Action’s Missouri federal committee, the organizations backing Scharf. The Club for Growth committee received $2.1 million from billionaire hedge fund chief Paul Singer, a significant donor to Leo’s network. Since July 25, Leo’s network has donated $2.5 million to Defend Missouri, while Singer chipped in another $500,000.

State attorneys general are a key focus for Leo and his network, because they are well-positioned to bring lawsuits before the Supreme Court. In 2022, the court’s conservative supermajority overturned Roe v. Wade and eliminated federal protections for abortion rights, in a case led by Mississippi’s Republican attorney general. Since 2014, Leo’s network has donated nearly $23 million to the Republican Attorneys General Association, according to a review of data compiled by ProPublica.

In Missouri, Leo and his network are boosting a lawyer who previously worked with him to paint the Supreme Court ruby red.

“Leonard Leo is a dear friend and mentor of mine, and I’m honored to have his support,” Scharf tells Rolling Stone. The candidate says he has known Leo — who co-chairs the Federalist Society, the national conservative lawyers network — since he was in law school.

If Scharf doesn’t win the AG race, he could have a solid plan B. Thanks to Scharf’s role in helping secure Trump a presidential immunity blanket at the Supreme Court, Scharf’s stock has shot up considerably among the MAGA political, legal, and policymaking elites in recent months. According to two sources familiar with the situation, a pair of Trump confidants — one an attorney, the other a media personality — have directly pitched the ex-president on the idea that Scharf would be a worthy choice for a senior Justice Department or White House role, if Trump wins in November.

Scharf was previously an aide to Missouri Gov. Eric Greitens (R), who resigned in 2018, and went to work for Leo’s Judicial Crisis Network — now known as the Concord Fund, the Leo group boosting his AG bid. He reportedly focused on judicial nominations and confirmations, including Kavanaugh’s to the Supreme Court.

According to his LinkedIn, Scharf worked for several months at Leo’s consulting firm, CRC Advisors, in 2020, before joining the Trump Justice Department as an assistant U.S. attorney for the Eastern District of Missouri. In fall of 2020, Scharf worked as a nominations counsel, supporting Barrett’s Supreme Court confirmation — which secured a 6-3 supermajority for conservatives.

After Missouri’s attorney general, Eric Schmitt, won his Senate seat, Leo’s allies reportedly pressed Gov. Mike Parson to appoint Scharf. He chose Bailey instead — and Leo’s network soon started funding Defend Missouri, the pro-Scharf Super PAC.

Bailey has been an ultra-conservative, partisan attorney general in his own right. He’s made a show out of suing to investigate the liberal watchdog group Media Matters in response to its reporting on X, formerly known as Twitter. The organization managed to block a similar investigative effort by Texas; that decision has been appealed.

And while the pro-Scharf Super PAC is accusing Bailey of being soft on crime, he’s attempted to block prisoners from being let out of jail after they were found innocent and exonerated, and judges ordered their release.

“You will not find someone harder on crime than me,” Scharf told The New York Times. “That having been said, actual innocence claims should be taken very seriously.”

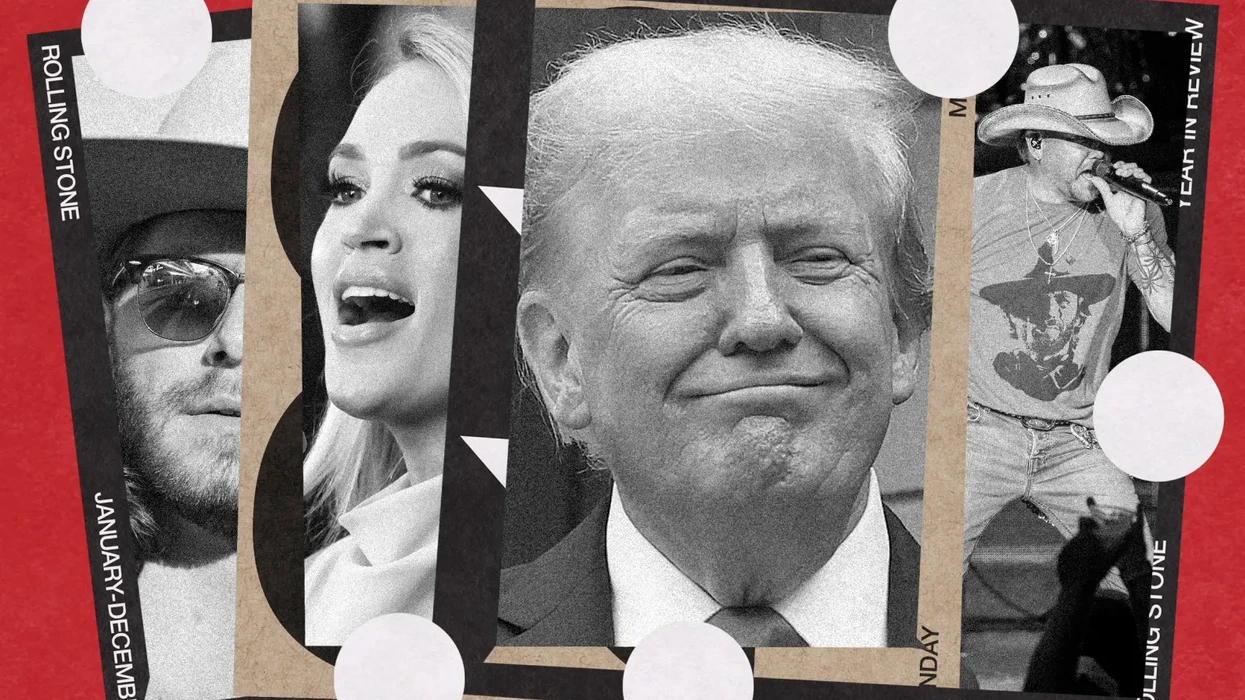

President Donald Trump discussing Venezuela at a press conference at Mar-a-Lago.

Why Venezuela Could Be a Turning Point in Gen Z’s Support for Trump

When Donald Trump called himself “the peace president” during his 2024 campaign, it was not just a slogan that my fellow Gen Z men and I took seriously, but also a promise we took personally. For a generation raised in the shadow of endless wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, it felt reassuring. It told us there was a new Republican Party that had learned from its failures and wouldn’t ask our generation to fight another war for regime change. That belief stood strong until the U.S. overthrew Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro.

Growing up in the long wake of the wars in Iraq in Afghanistan shaped how my generation learned to see Republicans. For us, “traditional” Republican foreign policy became synonymous with unnecessary conflicts that caused young people to bear the consequences. We heard how Iraq was sold to the public as a necessary war to destroy weapons of mass destruction, only to become a long conflict that defined the early adulthood of many millennials. Many of us grew up watching older siblings come home from deployments changed, and hearing teachers and coaches talk about friends who never fully came back. By the time we were old enough to pay attention, distrust of Bush-era Republicans wasn’t ideological, it was inherited from what we had heard.

As the 2024 election was rolling around, that dynamic had flipped. After watching wars in Ukraine and Gaza dominate headlines while Joe Biden was president, the Democrats were now the warmongers. My friends constantly told me how a vote for Kamala Harris was a vote to go to war. On the other hand, Donald Trump and the Republicans were the ones my friends thought could keep us safe. “I’m not voting for Trump because I love him,” one friend told me. “I’m voting for him because he cares about us and I don’t want to go fight in a stupid war.” For many of my friends, much of their vote came down to one question: Who was less likely to send us to fight? The answer to them was pretty clear.

Fast forward to now, and Venezuela has begun to complicate that belief. Even without talk of a draft or a formal declaration of war, the renewed focus on U.S. involvement and troops on the ground has brought back the same language of escalation my generation was taught to distrust. Young men online have been voicing the same worries, concerned that the ousting of Maduro mirrors the early stages of wars they were raised to fear. When I asked a friend what he thought about Venezuela, he shared that same sentiment. “This is how all these wars always start,” he told me. “They might try to make it sound like it’s not actually a war, but people our age always end up being the ones that pay the price for it.” For young men who supported Trump because they believed he represented a break from interventionist politics, Venezuela blurs the line between the “new” Republican Party they thought they were backing and the old one they were raised to reject.

For many young men, Venezuela has become a major part of a broader shift of how they view Trump. A recent poll from Speaking with American Men (SAM) found that Trump’s approval rating has fallen 10 percent among young men, with only 27 percent agreeing with the statement that Trump is “delivering for you”.

Gen Z men’s support of Trump was never about ideology or party loyalty, it was about the idea that he had their back and would fight for them. But that’s no longer the case. Recently, Trump proposed adding $500 billion to the military budget. Ideas like that will only hurt the president with young men. My friends don’t want more military spending that could get us entangled in foreign wars; they want a president who keeps them home and fights for their economic and social needs. As Trump pushes for a bigger military and more intervention abroad, the promise that once made him feel like a protector of young men now feels out of reach.

For my generation, Venezuela isn’t just another foreign policy dispute, it’s a conflict many young men worry they could be the ones sent to fight. Gen Z men didn’t support Trump because he was a Republican, but because they believed he was different from the old Republicans. He would be a president who would have their back, fight for their interests and keep them from fighting unnecessary wars. Now, that promise feels fragile, and the fear of being the ones asked to face the consequences has returned. For a generation raised on the effects of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, the idea of another war isn’t abstract, it’s personal.