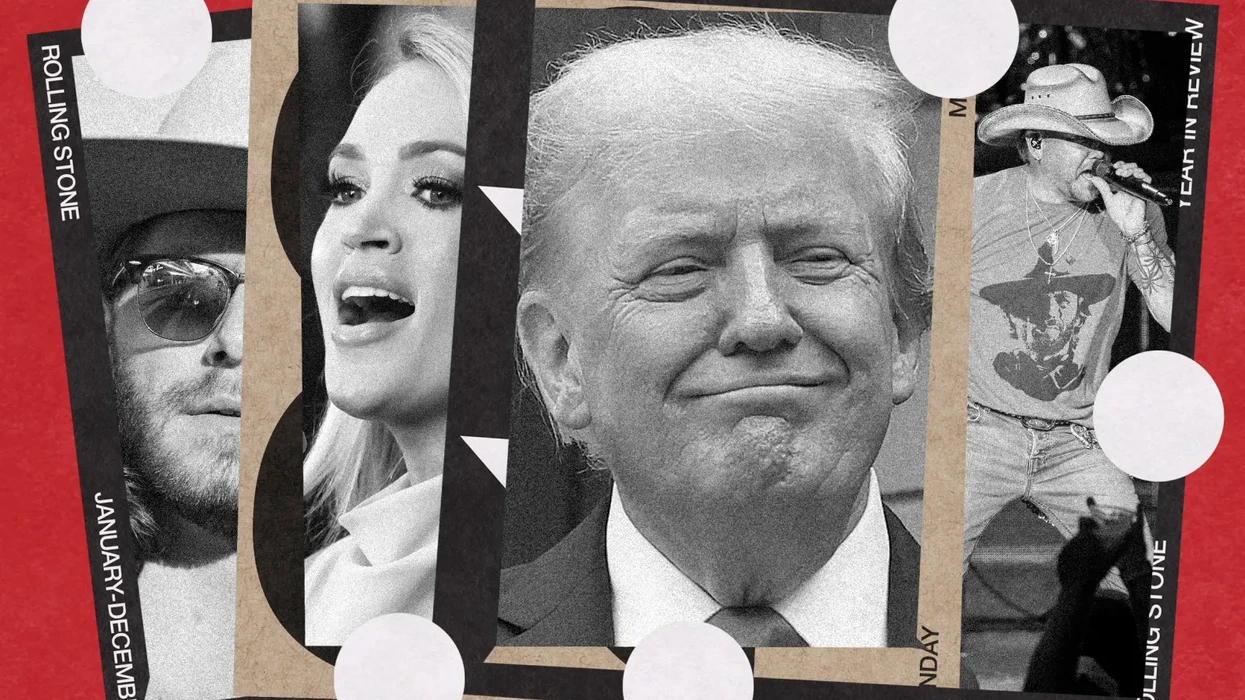

Canadian Prime Minister Mark Carney delivered a pointed critique of Donald Trump while speaking at the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland, as tension between Trump and America’s allies intensifies amid the president’s push to take control of Greenland.

“We are in the midst of a rupture, not a transition,” Carney said on Tuesday. “Over the past two decades, a series of crises in finance, health, energy, and geopolitics have laid bare the risks of extreme global integration. But more recently, great powers have begun using economic integration as weapons, tariffs as leverage, financial infrastructure as coercion, supply chains as vulnerabilities to be exploited. You cannot live within the lie of mutual benefit through integration when integration becomes the source of your subordination.”

Carney’s speech comes days after Trump announced a new round of tariffs against several of America’s European allies in an effort to force them to support his bid to annex Greenland, a territory of Denmark. Trump has meanwhile bashed NATO, even sharing a social media post on Tuesday alleging that the alliance of nations is a greater threat to the United States than Russia or China. The president has also recently shared memes depicting him planting the American flag on Greenland and of him and world leaders in the Oval Office next to a map with the American flag plastered over both Canada and Greenland. Trump on Sunday sent Norwegian Prime Minister Jonas Gahr Støre a letter in which he suggested he could take Greenland by force in response to not receiving the Nobel Peace Prize.

“We stand firmly with Greenland and Denmark and fully support their unique right to determine Greenland’s future,” Carney said to applause, adding that Canada “strongly opposes” tariffs over Greenland. Canada, like other nations, is moving to diversify its economic ties amid Trump’s erratic tariff agenda, signing a deal with China for low-cost electric vehicles last week. The European Union on Thursday stopped the approval of a trade deal it struck with the United States last summer.

Trump’s allies in government have repeatedly touted the need for the United States to dominate the Western Hemisphere, particularly in the wake of the U.S. military capturing Venezuelan dictator Nicolás Maduro earlier this month, effectively putting the U.S. in charge of the South American nation. (Trump even shared a social media post identifying him as the “Acting President of Venezuela.”) The administration’s attention quickly shifted to Greenland, and Canada is right to be worried — about what it could mean for NATO as well as the nation’s own sovereignty. Trump has frequently suggested that Canada become the “51st state,” and given the imperialistic moves Trump has already made this year it would be foolish to dismiss the possibility that he could have real designs on America’s neighbor to the north.

The Globe and Mail reported on Tuesday that the “Canadian Armed Forces have modeled a hypothetical U.S. military invasion of Canada and the country’s potential response,” citing two senior government officials. The officials said it was unlikely that Trump would order such an invasion, but that if it were to happen, “the military envisions unconventional warfare in which small groups of irregular military or armed civilians would resort to ambushes, sabotage, drone warfare, or hit-and-run tactics.”

The Globe and Mail reported earlier this week that Canada is considering sending troops to Greenland as a show of solidarity with Denmark, and Carney said in Davos that Canada is working with NATO allies to help secure the alliance’s northern and western flanks, including through “boots on the ground, boots on the ice.”

Carney wasn’t the only world leader to level a barely veiled criticism of Trump at the World Economic Forum. French President Emmanuel Macron spoke on Tuesday of a “world without rules, where international law is trampled underfoot, and where the only laws that seem to matter are of the strongest, and where imperial ambitions are resurfacing.” Macron referenced Russia’s war of aggression in Ukraine and conflict in the Middle East and Africa, as well as America’s trade wars, noting that Trump’s tariffs are “fundamentally unacceptable, especially when they are used as leverage against territorial sovereignty.”

“We prefer science to conspiracy theories, rule of law to rule of force, dialogue to threats,” Macron added later on X, echoing comments from his speech.

Trump spoke at White House on Tuesday to commemorate the anniversary of his return to the White House last January, and again he took a jab at NATO. “NATO has to treat us fairly,” he said. “The big fear I have with NATO is that we spend tremendous amounts of money with NATO. I know we’ll come to their rescue, but I really do question whether they’ll come to ours. I’m just saying.”

Trump added later that he “lost a lot of respect for Norway” because he didn’t win the Nobel Peace Prize after he “settled eight wars,” which he says was “easy.” When asked how far he is willing to go to acquire Greenland, Trump responded, “You’ll find out.”

Trump spoke today at Davos, reiterating his belief that America needs to control Greenland while claiming he won’t use force to take the Danish territory, which he referred to as “Iceland” multiple times during the speech. “So we want a piece of ice for world protection, and they won’t give it,” the president lamented, threatening to “remember” if Denmark doesn’t let the U.S. take control of Greenland.

Trump also took a jab at Carney. “Canada gets a lot of freebies from us. They should be grateful also but they’re not,” he said of Canada. “I watched your prime minister yesterday, he wasn’t so grateful. But they should be grateful to us. Canada lives because of the United States. Remember that, Mark, the next time you make your statements.”

This story was originally published by Rolling Stone US on Jan. 21, 2026.

War Is Peace: Trump’s Regime-Change Reversal

As American and Israeli rockets fly into Tehran, with the stated goal of regime change, anyone who bought into the self-evidently absurd idea of “Donald the Dove” ending America’s forever wars ought to be suffering from a bloody form of buyer’s remorse.

It was always bullshit. But that’s what the Trump team was selling hard. Take human ghoul Stephen Miller’s tweet days before the election: “Kamala = WWIII. Trump = Peace.”

The Trump team reads George Orwell’s 1984 like an owner’s manual and so of course “war is peace.” Their undermining of NATO and the dismantling of American alliances in favor of a “might makes right” foreign policy executed by a sycophantic kakistocracy is a guarantee of more war amid autocratic power grabs worldwide, with a side order of corrupt crony capitalism to profit from the chaos.

If you voted for Trump and believed him, this is on you. And that includes self-styled Palestinian peace activists who thought that Biden and Harris were the worst of all possible worlds and stayed home. We will no doubt see protests for the innocent lives lost in these strikes — but I’d have a lot more time for those folks if they were also seen protesting the estimated 20,000 to 30,000 Iranian lives snuffed out by murderous mullahs in the last few months alone.

The Islamic Republic of Iran has been despotic and dangerous from its inception. The Iranian people have been oppressed and denied basic freedoms for decades. But this is an extreme example of a war of choice. The American military strikes against Iran’s nuclear weapons facility last year were justified because Iran cannot be trusted with a nuclear weapon. That is true. But the much trumpeted total obliteration of those facilities is apparently not true — or so goes the justification for this war. And don’t forget that it was Trump who pulled the U.S. out of an Obama-era deal to stop Iran from developing weapons — arguing absurdly that the imperfect anti-nuke deal needed to be blown up to stop Iran from developing a bomb. Iran’s subsequent progress toward a bomb then created the rationale toward these strikes. This is a self-inflicted state of emergency. Peace is war and war is peace.

Pity the willful dupes in Congress who deluded themselves into thinking that Trump deserved the Nobel Peace Prize. They’ll probably rationalize that he would’ve been peaceful if he got the honor. Now it will be read as a cautionary tale for not sucking up. The chairman of the Board of Peace is now bored of peace. While Rand Paul remains admirably consistent, it’s Lindsey Graham who is pirouetting around the Senate floor while the Gimp Speaker Mike Johnson is unable to speak for the basic constitutional principles of separation of powers let alone authorization to go to war.

If you’re feeling shell-shocked trying to keep up with Operation Epstein Distraction, get ready for the inevitable next crisis — regime change without a plan for replacement. This is what the Trump administration did in Venezuela — kidnapping the socialist dictator Maduro but keeping his regime in place in exchange for crude oil access. The opposition is still in exile and its leader María Corina Machado gave her Nobel Peace Prize to Trump in exchange for exactly nothing.

One of the clear lessons of history is that if you don’t win the peace, you don’t win the war. The Saudis and their Sunni allies will back the U.S. and Iran because they hate the Shia Iranians (who, incidentally, are not Arabs), but beyond removing the Iranian regime, the plans for replacement and stabilization seem TBD — and with Trump’s inability to stay focused on anything beyond his immediate self-interest, solid plans are unlikely to emerge. Maybe a leader will come from the underground opposition; maybe it will be the Shah’s son, who has been living in the U.S. waiting for a restoration like many members of the diaspora. The upside is that Iran has a distinguished history and an accomplished Persian culture: The Islamists don’t represent the entirety of the people of Iran and never have.

But the path ahead will be messy at best. It will require concerted effort and civil commitment, not just an open call for private investment from Mar-a-Lago members. If the United States is now kidnapping and killing dictators without direct provocation, it establishes a dangerous precedent which will come back to bite us after demolishing our moral authority in the world.

It is the unexpected effects, the cascades of consequence where we cannot always plan ahead, that cause most responsible statesmen to try to keep the peace. But Trump has the carelessness of a rich-boy bully who can always buy or bluster his way out of trouble. He’s a con man who has found his ultimate mark in his followers, who fool themselves into thinking that a reflexive liar is the one man with the courage to tell the truth.

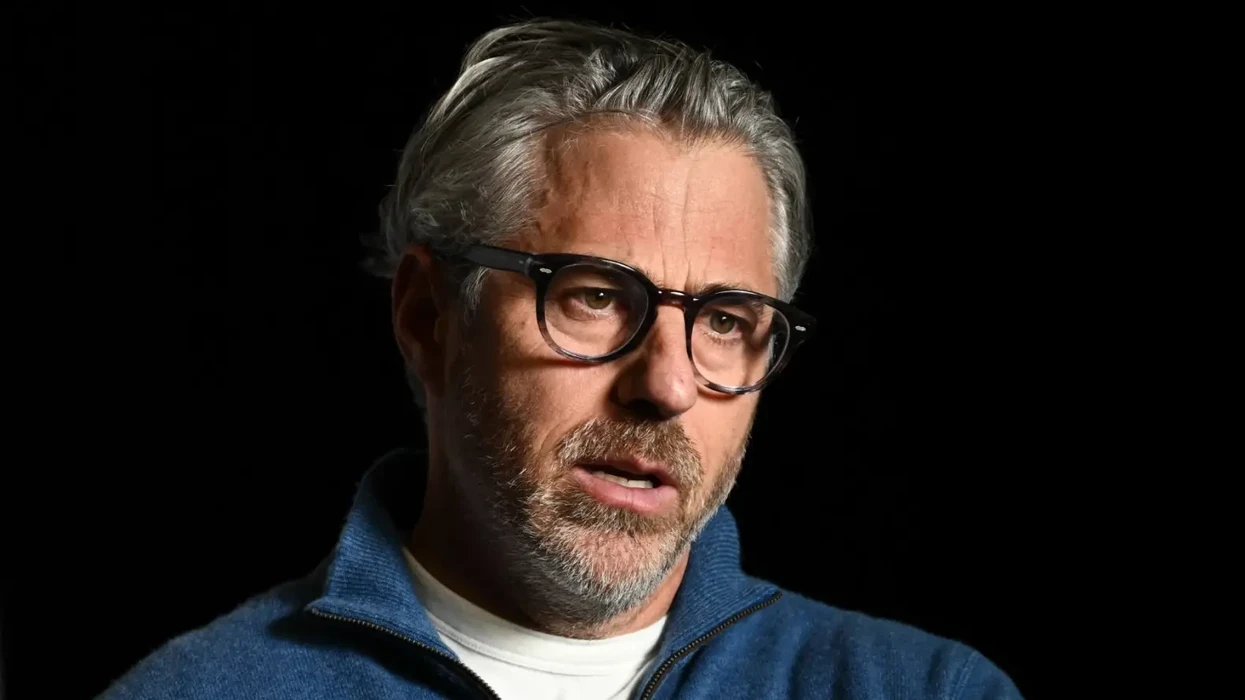

Perhaps the most prominent example is the vice president himself — a bright guy who not that long ago compared Trump to Hitler and a deadly narcotic but then convinced himself that careerism demanded an abrupt conversion. After all, he endorsed Trump less than two years ago with this very serious column headlined “Trump’s Best Foreign Policy? Not Starting Any Wars,” explaining, “He has my support in 2024 because I know he won’t recklessly send Americans to fight overseas.”