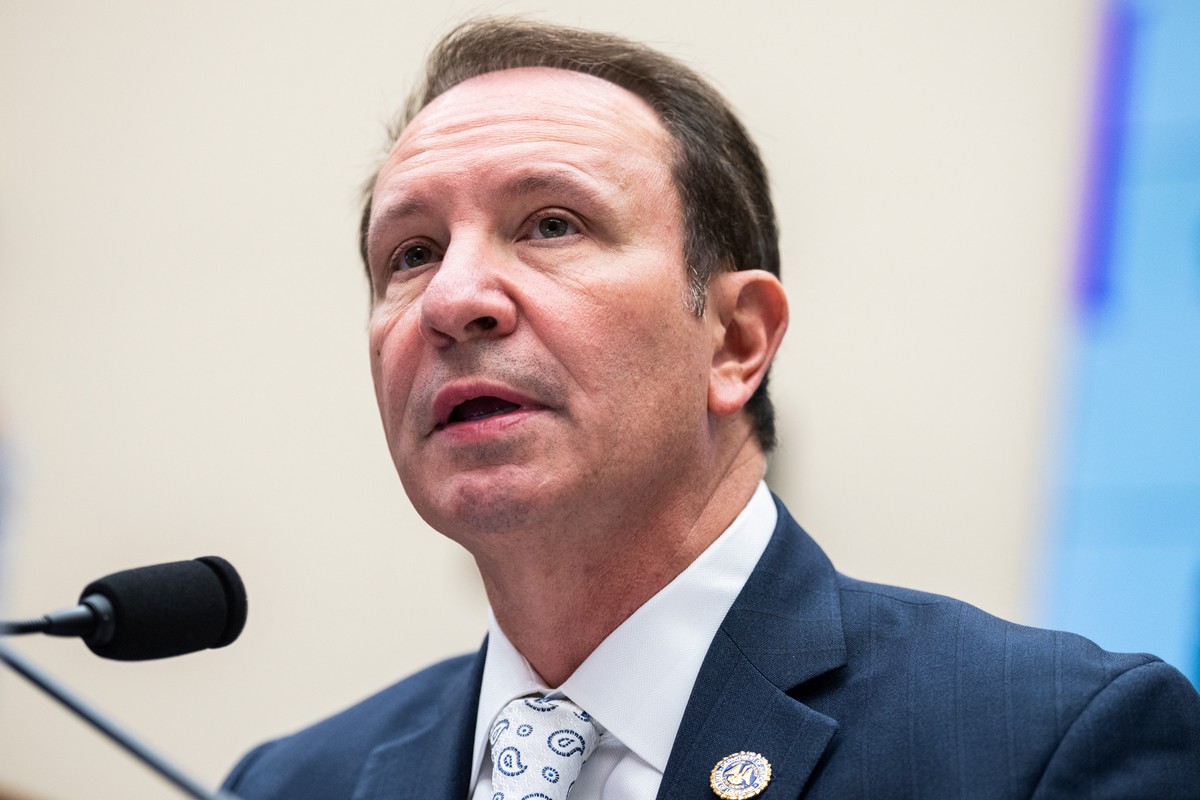

While defending Louisiana’s controversial new legislation requiring the Ten Commandments be displayed in all classrooms, including K-12 schools, colleges, and universities, Republican Gov. Jeff Landry and Attorney General Liz Murrill on Monday unveiled sample posters that feature liberal icons, including the late Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Hamilton playwright Lin-Manuel Miranda.

Louisiana passed its Ten Commandments law in June. The American Civil Liberties Union and other advocacy groups have filed a lawsuit arguing that the law violates “the separation of church and state and is blatantly unconstitutional.” At a press conference Monday, Murrill said she and the governor are requesting a federal court throw out what she describes as a “premature” lawsuit against the state, because the plaintiffs don’t claim to have seen any displays of the Ten Commandments yet in classrooms, so they “cannot prove they have any actual injury.” The state attorney general further argued the ACLU cannot show that every Ten Commandments display would be unconstitutional.

As examples, Landry and Murrill displayed large sample posters that Murrill said are “plainly constitutional” and could be placed in public school classrooms. There were a variety of posters, one targeting young children with classroom safety rules, one depicting Speaker Mike Johnson alongside a photo of the bust of Moses which is displayed in the House of Representatives.

Some of the posters seemed designed to make the Ten Commandments displays more palatable to liberals — or perhaps to bait them. Two have a quote from Ginsburg about great documents that provided the world “fine ideals and principles,” including the Ten Commandments and the Declaration of Independence.

Justice Ginsburg’s granddaughter Clara Spera says Louisiana is “misleading the public” by using Ginsburg’s quote, which was from a paper she wrote in 1946 when she was in eighth grade.

“The use of my grandmother’s image in Louisiana’s unconstitutional effort to display the Ten Commandments in public schools is misleading and an affront to her well-documented First Amendment jurisprudence,” Spera tells Rolling Stone in an email. “By placing the quote next to an official Supreme Court portrait of her in judicial robes and a jabot, Louisiana is misleading the public by suggesting that Justice Ginsburg made the statement about the Ten Commandments being among the world’s ‘four great documents’ while serving as a Supreme Court Justice.”

Spera, who is a reproductive rights attorney, cites McCreary County v. ACLU, where Ginsburg joined the majority opinion that held that Ten Commandments displays in Kentucky courthouses and public schools violated the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment. She continued “To me, and to others familiar with Justice Ginsburg’s legal writings and philosophy, there is no doubt that my grandmother would find that Louisiana’s effort to require public schools to display the Ten Commandments is a violation of the Constitution.”

Other posters have alternate commandments posted next to the Ten Commandments, such as one that displays Martin Luther King Jr.’s commandments of non-violence.

“There was this explosion of horror when the governor signed the law,” said Murrill. “I think that was a great overreaction and every one of these posters illustrates that.”

Murrill said the state’s Department of Justice sees these Ten Commandments posters as “teachable moments” for children.

One such teachable moment for school kids includes a side-by-side of Charlton Heston as Moses and a picture of Lin-Manuel Miranda from Hamilton. The Ten Commandments are placed next to the Ten Duel Commandments from the Broadway musical, which detail the rules of a gunfight at dawn. “Get some pistols and a doctor,” says one line. “Count 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10 paces. Fire!”

Yes, these duel commandments are placed next to the biblical decree: “Thou shalt not kill.”

The posters “show different ways that we can comply with the law and it isn’t going to cause the whole Constitution to cave under the weight of the law,” said Murrill. Under the Louisiana law, the Ten Commandments must be depicted “in a large, easily readable font,” and the poster can be no smaller than 11 by 14 inches. Posters will be donated to classrooms to be displayed.

At the press conference, Landry was asked about atheist parents who might not want their children to see the Ten Commandments at school, “If they find them so vulgar, tell the child not to look at them,” he replied.

“I did not know that the Ten Commandments was such a bad way for someone to live their life,” said Landry. “Many religions share and recognize [them] as a whole, so, really and truly, I don’t see what the whole big fuss is about.”

Landry has previously said he “can’t wait to be sued” for the Ten Commandments law, which he signed in June. Landry has also stated he thinks if the Ten Commandments had been displayed in Thomas Matthew Crooks’ classroom, he may have not attempted to assassinate former President Donald Trump. The legislation is scheduled to take effect in January 2025.

“The First Amendment of the U.S. Constitution protects everyone’s religious freedom.” Alanah Odoms, executive director at the ACLU of Louisiana, told Rolling Stone in a statement. “The Louisiana Legislature cannot impose its religious beliefs on our children and families. Forcing all public-school students to follow the state’s version of the Ten Commandments, regardless of their own beliefs, is unconstitutional. We will not back down from this fight and eagerly await our day in court.”

In 1948, the Supreme Court ruled in Everson v. Board of Education that “the First Amendment has erected a wall between church and state.” In 1962, the high court said officially-sponsored prayer in school was unconstitutional. When Louisiana tried to enact a law saying evolutionism and creationism should receive “balanced treatment” in science classes, the Supreme Court struck it down in 1987. However, recently, the court’s conservative supermajority in 2022 ruled in favor of a Christian public school football coach who prayed with his students, blurring the line between church and state at schools.

Murrill says she perceived the state legislature passing the Ten Commandments law as a statement that legislators and the people they represent are frustrated. “They are frustrated with the lack of discipline in our schools,” she said. “They’re frustrated with the inability of the whole system at this point to impose some rules of order, and so they went back to one of the original lawmakers who was Moses.”

Murrill said she believes the law will help “advance the education mission” in the state. Louisiana’s educational system is ranked one of the lowest in the nation, coming in at 40.

Landry, who was previously attorney general, became governor of the state in January. Under his watch, the state has passed a slew of conservative educational bills, including the Ten Commandments law, a “Don’t Say Gay” bill, and a measure allowing private school tuition vouchers.

This story has been updated to include comment from Clara Spera, Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s granddaughter.

President Donald Trump discussing Venezuela at a press conference at Mar-a-Lago.

Why Venezuela Could Be a Turning Point in Gen Z’s Support for Trump

When Donald Trump called himself “the peace president” during his 2024 campaign, it was not just a slogan that my fellow Gen Z men and I took seriously, but also a promise we took personally. For a generation raised in the shadow of endless wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, it felt reassuring. It told us there was a new Republican Party that had learned from its failures and wouldn’t ask our generation to fight another war for regime change. That belief stood strong until the U.S. overthrew Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro.

Growing up in the long wake of the wars in Iraq in Afghanistan shaped how my generation learned to see Republicans. For us, “traditional” Republican foreign policy became synonymous with unnecessary conflicts that caused young people to bear the consequences. We heard how Iraq was sold to the public as a necessary war to destroy weapons of mass destruction, only to become a long conflict that defined the early adulthood of many millennials. Many of us grew up watching older siblings come home from deployments changed, and hearing teachers and coaches talk about friends who never fully came back. By the time we were old enough to pay attention, distrust of Bush-era Republicans wasn’t ideological, it was inherited from what we had heard.

As the 2024 election was rolling around, that dynamic had flipped. After watching wars in Ukraine and Gaza dominate headlines while Joe Biden was president, the Democrats were now the warmongers. My friends constantly told me how a vote for Kamala Harris was a vote to go to war. On the other hand, Donald Trump and the Republicans were the ones my friends thought could keep us safe. “I’m not voting for Trump because I love him,” one friend told me. “I’m voting for him because he cares about us and I don’t want to go fight in a stupid war.” For many of my friends, much of their vote came down to one question: Who was less likely to send us to fight? The answer to them was pretty clear.

Fast forward to now, and Venezuela has begun to complicate that belief. Even without talk of a draft or a formal declaration of war, the renewed focus on U.S. involvement and troops on the ground has brought back the same language of escalation my generation was taught to distrust. Young men online have been voicing the same worries, concerned that the ousting of Maduro mirrors the early stages of wars they were raised to fear. When I asked a friend what he thought about Venezuela, he shared that same sentiment. “This is how all these wars always start,” he told me. “They might try to make it sound like it’s not actually a war, but people our age always end up being the ones that pay the price for it.” For young men who supported Trump because they believed he represented a break from interventionist politics, Venezuela blurs the line between the “new” Republican Party they thought they were backing and the old one they were raised to reject.

For many young men, Venezuela has become a major part of a broader shift of how they view Trump. A recent poll from Speaking with American Men (SAM) found that Trump’s approval rating has fallen 10 percent among young men, with only 27 percent agreeing with the statement that Trump is “delivering for you”.

Gen Z men’s support of Trump was never about ideology or party loyalty, it was about the idea that he had their back and would fight for them. But that’s no longer the case. Recently, Trump proposed adding $500 billion to the military budget. Ideas like that will only hurt the president with young men. My friends don’t want more military spending that could get us entangled in foreign wars; they want a president who keeps them home and fights for their economic and social needs. As Trump pushes for a bigger military and more intervention abroad, the promise that once made him feel like a protector of young men now feels out of reach.

For my generation, Venezuela isn’t just another foreign policy dispute, it’s a conflict many young men worry they could be the ones sent to fight. Gen Z men didn’t support Trump because he was a Republican, but because they believed he was different from the old Republicans. He would be a president who would have their back, fight for their interests and keep them from fighting unnecessary wars. Now, that promise feels fragile, and the fear of being the ones asked to face the consequences has returned. For a generation raised on the effects of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, the idea of another war isn’t abstract, it’s personal.