ATLANTA — Two weeks ago, staffers working for the major Democratic campaigns and party committees were demoralized and depressed, their dream jobs transformed into a joyless death march. Donations were drying up, while candidates and elected officials were speaking openly and with a grave certainty that the party was destined for an extinction-level electoral wipeout in November.

In the world of two weeks ago, the graphic Democratic euphoria on display in Atlanta Tuesday would have been almost inconceivable: a Division I basketball arena packed so full of ecstatic supporters that the fire marshal was refusing to let anyone else in. There was simply no space left. Ticket holders, credentialed press, elected officials who failed to make it inside the Georgia Convocation Center lined the barricades along Capitol Avenue, in the 91-degree heat, to watch a succession of celebrities on the Jumbotron.

It’s been just ten days since Joe Biden withdrew from the 2024 presidential campaign, and the vibe shift was spectacular. Vice President Kamala Harris’ Atlanta rally — the first bonafide campaign event since she took control of the Democratic ticket — had the energy of a homecoming rally. Stacey Abrams, Sen. Jon Ossoff, and Sen. Raphael Warnock spoke. Megan Thee Stallion stunted on stage, a “Hotties for Harris” banner billowing in the stands behind her. “I know my ladies in the crowd love their bodies,” she said. “And if you want to keep loving your body, you know who to vote for.” Quavo of Migos introduced the guy who introduced the vice president.

Peggy Golden traveled from her home in Savannah to be here: ”This is history,” she says. Golden is going to be 79 in December; she was born before the Civil Rights movement began. “I was brought up on a plantation,” she says. Her parents were a cook and caretaker. “I didn’t expect it to happen in my lifetime — and, hey, here it is,” she says of seeing a woman — a black woman — become president. “I feel it in my bones that it’s going to happen.”

But for all the excitement — and there seemed to be an endless supply of it in Atlanta — some attendees were still reeling from the political whiplash of the last few weeks. “I loved Biden and I was heartbroken when he dropped out of the race,” Lynda Cosby-Pinnock says. And she cautions Harris still has work to do to convince members of her own community she deserves their support, “Some people say they don’t know who she is, they’re not sure what she stands for,” she says.

Sydney Rhodes, a 28-year-old influencer, says she was always going to vote for the Democratic candidate: “I would vote for anybody besides Donald Trump and Project 2025.” But, she adds, “I think a lot of people are unsure because of the quick switch, and I hear a lot of people talk about her past as a prosecutor.”

Harris, for her part, is not shying away from her history as a prosecutor, district attorney, or attorney general. On stage in Atlanta, she lead with what has become her signature line: “In those roles, I took on perpetrators of all kinds: predators who abused women, fraudsters who ripped off consumers, cheaters who broke the rules for their own gain — so hear me when I say I know Donald Trump’s type.”

And in Atlanta, Harris showed a new willingness to place, at the center of the campaign, an issue Republicans are convinced is her biggest weakness: immigration.

“I was the attorney general of a border state,” Harris said on stage on Tuesday. “In that job I walked underground tunnels between the United States and Mexico on that border with law enforcement officers. I went after transnational gangs, drug cartels and human traffickers that came into our country illegally. I prosecuted them in case after case, and I won. Donald Trump, on the other hand, has been talking a big game about securing our border, but he does not walk the walk. Or, as my friend Quavo would say, he does not walk it like he talks it.”

Biden — with Harris’ help — won Georgia in 2020, but it will be a heavier lift four years later: As Rolling Stone has reported, Trump’s allies’ have transformed the state into a “laboratory” for strategies to contest the 2024 election, as one source close to the former president put it. Georgia Republicans have enacted a sweeping voter suppression law, empowered activists to file mass challenges to residents’ voter registrations, and packed the state and county election boards with Trump devotees who both believe his lies about the 2020 election and who have shown an increasing willingness to refuse to certify election results.

By launching her campaign in Atlanta, the Harris campaign was sending a clear signal: They intend to compete everywhere, including in states that seemed, two weeks ago, to be slipping out of their grip.

According to the campaign, more than 7,500 have signed up to volunteer in Georgia in the last week alone. In a call with reporters ahead of the launch, a Georgia state director for the Harris campaign reported that they’ve hired more than 170 Democratic staffers across 24 offices around the state — the largest in-state operation of a Democratic presidential campaign, she said, ever. And when she touched down in Atlanta on Tuesday afternoon, it was the sixth time Vice President Harris has traveled to Georgia this year, and her 15th trip since taking office in 2020.

“I am very clear: the path to the White House runs right through this state,” Harris said on Tuesday. “You all helped us win in 2020 — and we’re going to do it again in 2024.”

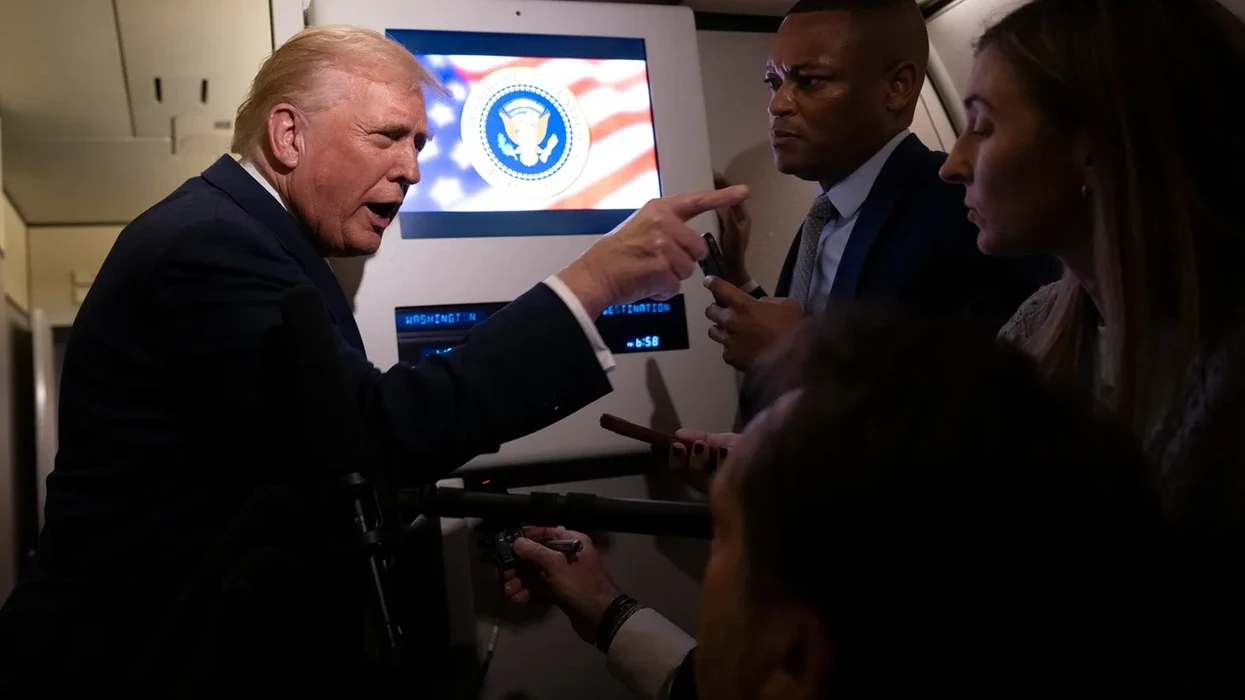

President Donald Trump discussing Venezuela at a press conference at Mar-a-Lago.

Why Venezuela Could Be a Turning Point in Gen Z’s Support for Trump

When Donald Trump called himself “the peace president” during his 2024 campaign, it was not just a slogan that my fellow Gen Z men and I took seriously, but also a promise we took personally. For a generation raised in the shadow of endless wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, it felt reassuring. It told us there was a new Republican Party that had learned from its failures and wouldn’t ask our generation to fight another war for regime change. That belief stood strong until the U.S. overthrew Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro.

Growing up in the long wake of the wars in Iraq in Afghanistan shaped how my generation learned to see Republicans. For us, “traditional” Republican foreign policy became synonymous with unnecessary conflicts that caused young people to bear the consequences. We heard how Iraq was sold to the public as a necessary war to destroy weapons of mass destruction, only to become a long conflict that defined the early adulthood of many millennials. Many of us grew up watching older siblings come home from deployments changed, and hearing teachers and coaches talk about friends who never fully came back. By the time we were old enough to pay attention, distrust of Bush-era Republicans wasn’t ideological, it was inherited from what we had heard.

As the 2024 election was rolling around, that dynamic had flipped. After watching wars in Ukraine and Gaza dominate headlines while Joe Biden was president, the Democrats were now the warmongers. My friends constantly told me how a vote for Kamala Harris was a vote to go to war. On the other hand, Donald Trump and the Republicans were the ones my friends thought could keep us safe. “I’m not voting for Trump because I love him,” one friend told me. “I’m voting for him because he cares about us and I don’t want to go fight in a stupid war.” For many of my friends, much of their vote came down to one question: Who was less likely to send us to fight? The answer to them was pretty clear.

Fast forward to now, and Venezuela has begun to complicate that belief. Even without talk of a draft or a formal declaration of war, the renewed focus on U.S. involvement and troops on the ground has brought back the same language of escalation my generation was taught to distrust. Young men online have been voicing the same worries, concerned that the ousting of Maduro mirrors the early stages of wars they were raised to fear. When I asked a friend what he thought about Venezuela, he shared that same sentiment. “This is how all these wars always start,” he told me. “They might try to make it sound like it’s not actually a war, but people our age always end up being the ones that pay the price for it.” For young men who supported Trump because they believed he represented a break from interventionist politics, Venezuela blurs the line between the “new” Republican Party they thought they were backing and the old one they were raised to reject.

For many young men, Venezuela has become a major part of a broader shift of how they view Trump. A recent poll from Speaking with American Men (SAM) found that Trump’s approval rating has fallen 10 percent among young men, with only 27 percent agreeing with the statement that Trump is “delivering for you”.

Gen Z men’s support of Trump was never about ideology or party loyalty, it was about the idea that he had their back and would fight for them. But that’s no longer the case. Recently, Trump proposed adding $500 billion to the military budget. Ideas like that will only hurt the president with young men. My friends don’t want more military spending that could get us entangled in foreign wars; they want a president who keeps them home and fights for their economic and social needs. As Trump pushes for a bigger military and more intervention abroad, the promise that once made him feel like a protector of young men now feels out of reach.

For my generation, Venezuela isn’t just another foreign policy dispute, it’s a conflict many young men worry they could be the ones sent to fight. Gen Z men didn’t support Trump because he was a Republican, but because they believed he was different from the old Republicans. He would be a president who would have their back, fight for their interests and keep them from fighting unnecessary wars. Now, that promise feels fragile, and the fear of being the ones asked to face the consequences has returned. For a generation raised on the effects of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, the idea of another war isn’t abstract, it’s personal.