Medicare has completed its first-ever negotiations with pharmaceutical companies over drug prices. Though only 10 drugs were part of the initial program, the Biden administration announced on Thursday that Medicare will save $6 billion and Americans will save $1.5 billion in out-of-pocket costs in the program’s first year.

Congress for decades prohibited Medicare from negotiating drug prices, something that virtually all other countries do. It’s a chief reason why drug prices are two to four times higher in the United States than in other wealthy countries. The negotiated price list released by the administration on Thursday shows what Americans have been missing out on: Medicare will pay less than half of the current list prices on nine of the first 10 drugs that were included in the program.

“For years, millions of Americans were forced to choose between paying for medications or putting food on the table, while Big Pharma blocked Medicare from being able to negotiate prices on behalf of seniors and people with disabilities,” President Joe Biden said in a statement. “But we fought back — and won.”

The fight is far from over: The negotiated prices will go into effect in 2026; several drugmakers and lobbying groups have sued to try to block the Medicare negotiation program, while Republican lawmakers are eager to repeal it.

The pharmaceutical industry is one of the most powerful and well-funded interest groups in Washington. Its lobbyists have long argued that negotiating drug prices would harm patients, limit access to medicines, and stifle innovation, even though the U.S. government helps fund research and development on all drugs that are approved for sale.

The basic reality is that Americans have been forced to pay the world’s highest prices for lifesaving products they helped finance. This status quo remains, but under Biden, Democrats finally fulfilled their longtime pledge to allow Medicare to negotiate drug prices. Some conservative Democrats helped water down the provision — limiting the number and types of drugs that would be subject to negotiation, and who will benefit — but the program’s successful inclusion as part of the 2022 Inflation Reduction Act was historic — and it opens the door to further expansions down the line.

During this year’s State of the Union speech, for instance, Biden called on Congress to “give Medicare the power to negotiate lower prices for 500 drugs over the next decade.” During her first campaign rally as the presumptive Democratic presidential nominee, Vice President Kamala Harris pledged to “take on Big Pharma to cap prescription drug costs for all Americans.”

Biden and Harris will hold a joint event in Maryland on Thursday touting the administration’s efforts to lower costs for the American people. The Harris campaign said she will announce a policy proposal on Friday pertaining to prescription drug costs.

Per the terms of the IRA, the Medicare drug negotiation program started with 10 expensive, older drugs that have no generic competition despite being on the market for at least nine years. The first round included drugs used to prevent blood clotting, reduce the risk of stroke, and treat diabetes, heart failure, blood cancers, Crohn’s disease, and plaque psoriasis.

As The Lever previously reported, the 10 drugs have all been sold in other countries at far lower prices.

One such drug is Januvia, a pill from Merck that helps adults with type 2 diabetes lower their blood sugar levels. A 2019 report by House Democrats found that Januvia was priced 1,000 percent higher in the U.S. than in international markets on average. Notably, the U.S. National Institutes of Health provided $228 million in funding for research prior to Januvia’s approval.

According to the Biden administration’s negotiated price list, the 2023 list price for a 30-day supply of Januvia was $527. In 2026, Medicare will instead pay $113 — or 79 percent less.

Xavier Becerra, Health and Human Services Secretary, celebrated the price negotiations in an interview with Rolling Stone, noting that the U.S. is going to save billions on “just this first negotiation on 10 drugs,” when there thousands of drugs covered under Medicare.

“If you look at it, if we can bring [one] price down by some 79 percent, why have we been paying these high prices so long, and how much should we actually be paying, and how many more drugs will we find that we can reduce the price of, if we just expand this program?” he said.

Merck launched the first lawsuit to block the Biden administration’s Medicare drug negotiation program, calling it “tantamount to extortion” and arguing that “it violates the Constitution.” Several drug industry lawsuits seeking to block the drug negotiation program have failed. Merck’s case is still pending.

“Every company that is suing us is also negotiating with us,” said Becerra. “Every company that negotiated with us agreed on a price. In some cases, we accepted an offer or counter offer that they came up with, and in the other cases, they accepted the offer [or] counter offer that we came up with. But either way, they agreed.”

He added, “We voluntarily came to an agreement on the price — even though they are suing us. And by the way, every lawsuit that they have filed so far, they haven’t won one.”

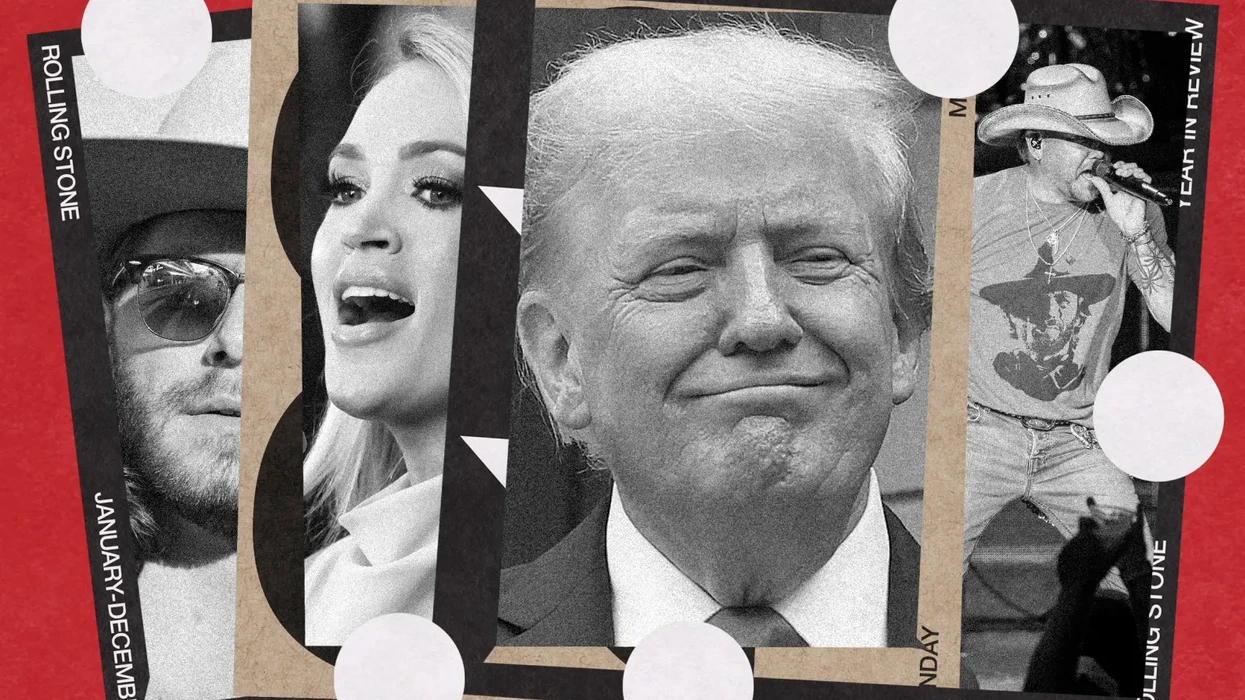

President Donald Trump discussing Venezuela at a press conference at Mar-a-Lago.

Why Venezuela Could Be a Turning Point in Gen Z’s Support for Trump

When Donald Trump called himself “the peace president” during his 2024 campaign, it was not just a slogan that my fellow Gen Z men and I took seriously, but also a promise we took personally. For a generation raised in the shadow of endless wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, it felt reassuring. It told us there was a new Republican Party that had learned from its failures and wouldn’t ask our generation to fight another war for regime change. That belief stood strong until the U.S. overthrew Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro.

Growing up in the long wake of the wars in Iraq in Afghanistan shaped how my generation learned to see Republicans. For us, “traditional” Republican foreign policy became synonymous with unnecessary conflicts that caused young people to bear the consequences. We heard how Iraq was sold to the public as a necessary war to destroy weapons of mass destruction, only to become a long conflict that defined the early adulthood of many millennials. Many of us grew up watching older siblings come home from deployments changed, and hearing teachers and coaches talk about friends who never fully came back. By the time we were old enough to pay attention, distrust of Bush-era Republicans wasn’t ideological, it was inherited from what we had heard.

As the 2024 election was rolling around, that dynamic had flipped. After watching wars in Ukraine and Gaza dominate headlines while Joe Biden was president, the Democrats were now the warmongers. My friends constantly told me how a vote for Kamala Harris was a vote to go to war. On the other hand, Donald Trump and the Republicans were the ones my friends thought could keep us safe. “I’m not voting for Trump because I love him,” one friend told me. “I’m voting for him because he cares about us and I don’t want to go fight in a stupid war.” For many of my friends, much of their vote came down to one question: Who was less likely to send us to fight? The answer to them was pretty clear.

Fast forward to now, and Venezuela has begun to complicate that belief. Even without talk of a draft or a formal declaration of war, the renewed focus on U.S. involvement and troops on the ground has brought back the same language of escalation my generation was taught to distrust. Young men online have been voicing the same worries, concerned that the ousting of Maduro mirrors the early stages of wars they were raised to fear. When I asked a friend what he thought about Venezuela, he shared that same sentiment. “This is how all these wars always start,” he told me. “They might try to make it sound like it’s not actually a war, but people our age always end up being the ones that pay the price for it.” For young men who supported Trump because they believed he represented a break from interventionist politics, Venezuela blurs the line between the “new” Republican Party they thought they were backing and the old one they were raised to reject.

For many young men, Venezuela has become a major part of a broader shift of how they view Trump. A recent poll from Speaking with American Men (SAM) found that Trump’s approval rating has fallen 10 percent among young men, with only 27 percent agreeing with the statement that Trump is “delivering for you”.

Gen Z men’s support of Trump was never about ideology or party loyalty, it was about the idea that he had their back and would fight for them. But that’s no longer the case. Recently, Trump proposed adding $500 billion to the military budget. Ideas like that will only hurt the president with young men. My friends don’t want more military spending that could get us entangled in foreign wars; they want a president who keeps them home and fights for their economic and social needs. As Trump pushes for a bigger military and more intervention abroad, the promise that once made him feel like a protector of young men now feels out of reach.

For my generation, Venezuela isn’t just another foreign policy dispute, it’s a conflict many young men worry they could be the ones sent to fight. Gen Z men didn’t support Trump because he was a Republican, but because they believed he was different from the old Republicans. He would be a president who would have their back, fight for their interests and keep them from fighting unnecessary wars. Now, that promise feels fragile, and the fear of being the ones asked to face the consequences has returned. For a generation raised on the effects of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, the idea of another war isn’t abstract, it’s personal.