Hours after executing the raid to capture Venezuelan dictator Nicolas Maduro, the heads of the United States government gathered before the press not to exalt democracy or detail their plan for Venezuelan self-determination, but to make clear that they intend to bleed the nation of its oil reserves.

President Donald Trump is “deadly serious about getting back the oil that was stolen from us,” Secretary of Defense Pete Hegseth warned. The president himself repeatedly told reporters that the South American nation — home to some of the largest oil reserves on the planet — “stole our oil.”

“We’re going to have a presence in Venezuela as it pertains to oil,” Trump said. “We’re going to be taking out a tremendous amount of wealth out of the ground.”

Trump did not notify Congress of his plans to depose Maduro, but he says he did tip off American oil executives. On Tuesday, Trump announced that Venezuela would be “turning over between 30 and 50 MILLION Barrels of High Quality, Sanctioned Oil, to the United States of America.” The president also clarified that the seized oil would be “sold at its Market Price, and that money will be controlled by me, as President of the United States of America, to ensure it is used to benefit the people of Venezuela and the United States!”The arrangement is unprecedented even in the history of American resource imperialism, and experts warn that the administration’s move to take control of Venezuela’s oil production, seemingly with the intent of keeping the profits, will be incredibly difficult, risks triggering a full internal collapse within Venezuela, and could turn violent.

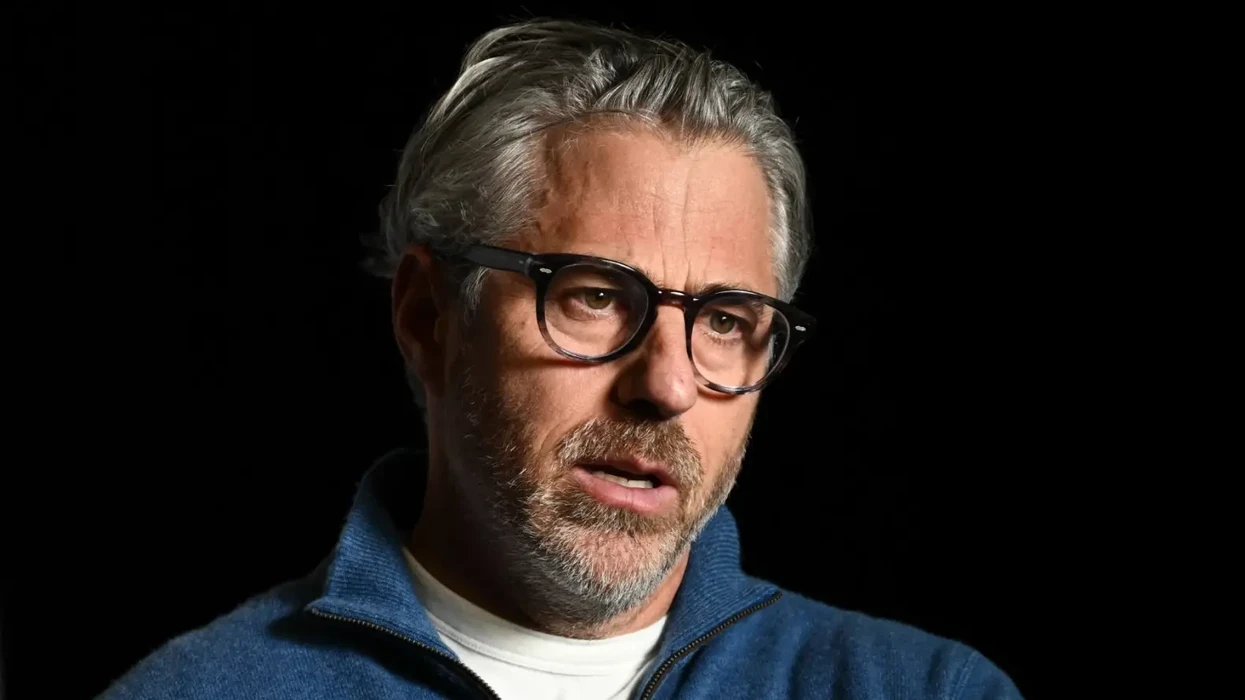

“There’s absolutely no doubt this is 100 percent driven by President Trump’s desire that Venezuelan oil is now owned, run — and therefore the profits are controlled — by the White House,” Robert Pape, professor of political science at the University of Chicago, tells Rolling Stone. In Pape’s view, however, “Trump will never control Venezuela’s oil.”

The United States does not actually have a legal claim to energy resources under Venezuela. As a matter of international law, a government cannot unilaterally claim ownership over the natural resources of another nation. At the center of Trump’s claims of “theft” are billions in unpaid settlement funds international courts granted to American oil companies after Maduro’s predecessor, Hugo Chávez, seized assets belonging to foreign oil companies amid a push to fully nationalize the industry in 2007.

To have a single industry play such a large role in the economy of a nation can give “foreign companies a huge amount of political veto power,” says Patrick Iber, Latin American historian and professor of history at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. The various waves of economic nationalism that shaped Venezuela’s energy sector often followed political movements opposing foreign intervention. Negotiating relationships between states and foreign companies is “difficult,” Iber adds, because when a nation becomes highly dependent on one export, allowing international control to take root can feel like a compromise of their sovereignty.

Venezuela’s economic health has been directly attached to the success of its petroleum production for almost a century. In 1976, President Carlos Andrés Pérez partially nationalized Venezuela’s then-thriving oil industry, creating Petróleos de Venezuela (PDVSA). The move took place at a time when many global oil producers were moving toward state-controlled models, and Venezuela continued to work with foreign energy companies. The 2007 takeover under Chavez was the inflection point that would eventually lead to the near total collapse of Venezuela’s economy. Companies fled Venezuela just as oil prices dropped globally. Expensive social projects proposed by Chavez depended on oil revenue for funding, which became more scarce as the infrastructure abandoned by major energy corporations fell into disuse and disrepair. Collapsing revenue, as well as overspending, corruption, and hyperinflation would ultimately destroy the national economy.

In deposing and arresting Maduro, the Trump administration has refused to endorse members of the opposition who credibly defeated the Venezuelan despot in the nation’s 2024 elections. The nation will instead be governed — at least as the administration is presenting it — by the remnants of Maduro’s government and inner circle, under the control and supervision of Hegseth, Secretary of State Marco Rubio, and White House Deputy Chief of Staff Stephen Miller. The administration will throw open the door to American oil companies interested in extracting the thick crude of Venezuela’s under-tapped reserves. The Venezuelan government will likely acquiesce to whatever arrangements the Trump administration demands. Trump said earlier this week that Maduro’s vice president, Delcy Rodríguez, told Rubio that she’d do whatever the U.S. wants. “She was quite gracious,” Trump said, “but she really doesn’t have a choice.” Trump told The New York Times on Wednesday that the U.S. could control Venezuela for years.

All in all, Trump’s government is preparing to write the next chapter of a decades-long tug of war over Venezuela’s oil fields.

“There’s a lot of unknowns here,” says Michael Paarlberg, associate fellow with the Institute for Policy Studies. He notes that what is happening is “not regime change — it is leadership change, but with the same regime in place, one that is just as repressive, just as corrupt, and willing to sell out the Venezuelan people that they’re all also continuing to repress anyway.” While Maduro has been replaced by Rodríguez, the factors destabilizing Venezuela remain largely in place. It might get ugly if the U.S. tries to dictate how the region’s oil is managed.

“There are already tons of places in Venezuela where the state does not have a legitimate monopoly on the use of force,” Iber explains. “The other way to think about the way that the Venezuelan economy works is as a series of fiefdoms that have been parceled out to regime allies to exploit resources — whether those are oil or gold mining — or where somebody in the military has control of an area, and skims the profits out of the mostly illegal operations that are happening there with a ton of exploitation.”

“Anything that happens to disrupt the networks that are doing that is going to produce internal strife,” he adds.

Pape, who has built his expertise around insurgencies and guerilla movements, agrees. “We already have the remnants of the colectivos” — pro-Maduro militias that have carried out arrests of journalists and cracked down on dissenters since the dictator’s capture — and factions of the Maduro government that will be “primed to keep that, the gold, the oil money, for themselves.”

Pape argues that while the United States has made a show of force in the seas around Venezuela, they have little to no hope of controlling the interior of the country without a robust ground force.

“I’ve advised every White House, including the first Trump administration,” he says, adding that the armada of about 10,000 Marines currently stationed in the Caribbean “would be very useful for perimeter defense, for controlling the area and space around the oil fields, and the oil infrastructure […] but they’re not going to be very good at preventing guerrilla warfare.”

The U.S. military is not trained to run oil fields, and any effort to capture, control, and rebuild Venezuela’s energy sector would require the participation of thousands of private contractors. The United States already has a reputation of imperial exploitation in Latin America, and experts like Pape worry that in an already unstable country, Trump’s loud declarations that the U.S. intends to commandeer their primary economic resource could place contractors and others brought in by the Trump administration to manage the takeover in the crosshairs of insurgent violence.

“This whole mission has a gigantic hole right in the middle of it, which is that this situation is not going to be safe for civilian contractors,” Pape says. “You will need hundreds, if not thousands, scattered over the oil fields for weeks and months to actually run the oil out in a way that America, the White House, will profit. This is just extremely unlikely to happen.”

Iber and Paarlberg agree that the situation is extremely fragile. Rodriguez, currently acting as interim president, will be facing pressure and potential violence from other factions of the Chavistas jockeying for power and upset over her public deal-making with the Trump administration.

“Anybody who is in charge of the country now has to tie together a really rickety system where a lot of people are on the edge of solvency and are operating through illegal networks,” Iber says. ”[This] could very easily escape out of the boundaries of what [Trump] thinks can be done.”