Russia’s army of online trolls seemed powerful after claims they may have helped Donald Trump win the presidency in 2016. But nearly eight years later, that troll army is struggling in the trenches of Russia’s war on Ukraine as it tries — and fails — to trick the world into buying the Kremlin’s talking points about the invasion.

That’s the conclusion of a new report by Facebook parent company Meta released on Wednesday. The Meta researchers say that over the past few years, they’ve seen “a consistent decline in the overall followings” of covert influence operations identified by the company.

Since his tanks rolled into Ukraine two years ago, Russian President Vladimir Putin has put the war at the forefront of his covert influence campaigns. But a lot has changed since the days when the Internet Research Agency, at the direction of Kremlin officials, promoted hacked Hillary Clinton campaign emails and sowed division along America’s cultural fault lines in the 2016 presidential election — including through paid Facebook ads. In the years that followed, and especially since the start of the latest war in Ukraine, Russia’s trolls have witnessed a decline in audiences, highlighting both the Kremlin’s continuing struggles in the conflict and the resilience of Western civil society.

The report found that since the start of the war, Russian troll operators have moved away from their previous, more labor-intensive tactics, which involved efforts to build up fleshed-out backstories for their fake personas. Instead, researchers saw Moscow’s troll farms shift to cranking out masses of “thinly-disguised, short-lived fake accounts,” in the hopes that one of them will get lucky and “stick” within the public consciousness.

Few, if any, were so lucky.

While Russian trolls have tried to create more accounts, pages, and groups on average than in previous years, the number of followers for them has actually fallen dramatically, according to Meta. That same decline is evident for Russia’s overt, state-backed propaganda outlets, which suffered “sustained lower levels of activity and engagement globally,” the social media company concluded.

For those that remained, the numbers have been grim. In the past year, the volume of posts from Russian government propaganda outlets on Meta platforms like Facebook and Instagram has declined 55 percent, while the audience for them dropped by a startling 94 percent, continuing a decline seen in the first year of Russia’s war in Ukraine.

Across a broad array of troll accounts and campaigns, Russian covert influence operations have largely stuck to a handful of key subjects when talking about Ukraine, suggesting more central direction from their employers. Meta researchers identified a number of consistent narratives pushed by the shadowy sock puppets. Key talking points have included bogus claims about U.S.-backed Ukrainian “bioweapons” labs, efforts to paint Ukraine as arming terrorist groups and stoke conflict between Kyiv and neighboring states, like Poland.

At the outset of Russia’s war on Ukraine, a number of European countries sanctioned or outright banned Russian government propaganda outlets like RT, Sputnik, and others, while in the U.S., RT America laid off its staff and closed its doors.

But Meta has also sought to limit the reach of remaining Russian official propaganda outlets with a series of “nudges” designed to limit the visibility of such posts, like bans on ads and labels identifying Russian government-linked accounts.

Meta researchers also reported that they were able to solve a yearlong mystery involving one of Russia’s longest-running covert troll campaigns, Secondary Infektion. The operation dates back to 2014 and has targeted dozens of countries in a host of languages, often using a mixture of forged official documents and screenshots to push pro-Russian and anti-Western narratives.

The group gained notoriety in the West when researchers linked it to a 2019 hack-and-leak operation aimed at disrupting the British general election.

Even with their high volume of posts and track record dating back years, the identities of those behind the activity has been a mystery until now. In their latest report, Meta researchers say they’ve solved at least part of that puzzle and attributed the group to “individuals associated with the Russian state.”

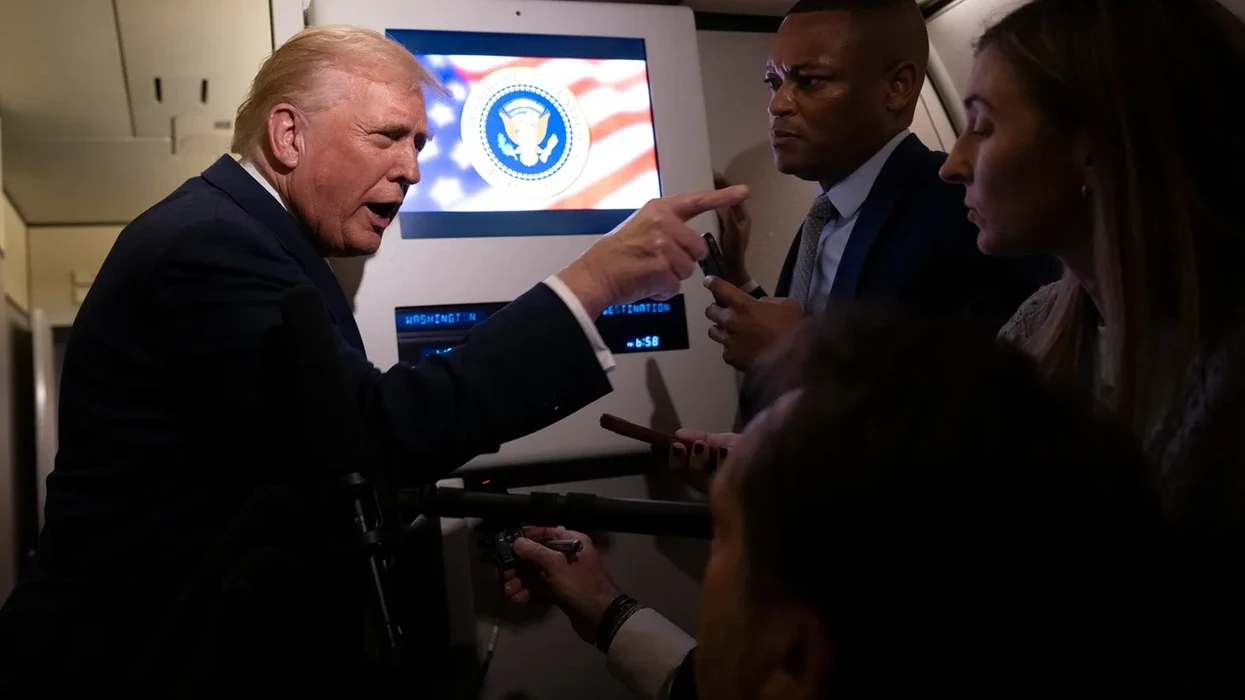

President Donald Trump discussing Venezuela at a press conference at Mar-a-Lago.

Why Venezuela Could Be a Turning Point in Gen Z’s Support for Trump

When Donald Trump called himself “the peace president” during his 2024 campaign, it was not just a slogan that my fellow Gen Z men and I took seriously, but also a promise we took personally. For a generation raised in the shadow of endless wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, it felt reassuring. It told us there was a new Republican Party that had learned from its failures and wouldn’t ask our generation to fight another war for regime change. That belief stood strong until the U.S. overthrew Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro.

Growing up in the long wake of the wars in Iraq in Afghanistan shaped how my generation learned to see Republicans. For us, “traditional” Republican foreign policy became synonymous with unnecessary conflicts that caused young people to bear the consequences. We heard how Iraq was sold to the public as a necessary war to destroy weapons of mass destruction, only to become a long conflict that defined the early adulthood of many millennials. Many of us grew up watching older siblings come home from deployments changed, and hearing teachers and coaches talk about friends who never fully came back. By the time we were old enough to pay attention, distrust of Bush-era Republicans wasn’t ideological, it was inherited from what we had heard.

As the 2024 election was rolling around, that dynamic had flipped. After watching wars in Ukraine and Gaza dominate headlines while Joe Biden was president, the Democrats were now the warmongers. My friends constantly told me how a vote for Kamala Harris was a vote to go to war. On the other hand, Donald Trump and the Republicans were the ones my friends thought could keep us safe. “I’m not voting for Trump because I love him,” one friend told me. “I’m voting for him because he cares about us and I don’t want to go fight in a stupid war.” For many of my friends, much of their vote came down to one question: Who was less likely to send us to fight? The answer to them was pretty clear.

Fast forward to now, and Venezuela has begun to complicate that belief. Even without talk of a draft or a formal declaration of war, the renewed focus on U.S. involvement and troops on the ground has brought back the same language of escalation my generation was taught to distrust. Young men online have been voicing the same worries, concerned that the ousting of Maduro mirrors the early stages of wars they were raised to fear. When I asked a friend what he thought about Venezuela, he shared that same sentiment. “This is how all these wars always start,” he told me. “They might try to make it sound like it’s not actually a war, but people our age always end up being the ones that pay the price for it.” For young men who supported Trump because they believed he represented a break from interventionist politics, Venezuela blurs the line between the “new” Republican Party they thought they were backing and the old one they were raised to reject.

For many young men, Venezuela has become a major part of a broader shift of how they view Trump. A recent poll from Speaking with American Men (SAM) found that Trump’s approval rating has fallen 10 percent among young men, with only 27 percent agreeing with the statement that Trump is “delivering for you”.

Gen Z men’s support of Trump was never about ideology or party loyalty, it was about the idea that he had their back and would fight for them. But that’s no longer the case. Recently, Trump proposed adding $500 billion to the military budget. Ideas like that will only hurt the president with young men. My friends don’t want more military spending that could get us entangled in foreign wars; they want a president who keeps them home and fights for their economic and social needs. As Trump pushes for a bigger military and more intervention abroad, the promise that once made him feel like a protector of young men now feels out of reach.

For my generation, Venezuela isn’t just another foreign policy dispute, it’s a conflict many young men worry they could be the ones sent to fight. Gen Z men didn’t support Trump because he was a Republican, but because they believed he was different from the old Republicans. He would be a president who would have their back, fight for their interests and keep them from fighting unnecessary wars. Now, that promise feels fragile, and the fear of being the ones asked to face the consequences has returned. For a generation raised on the effects of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, the idea of another war isn’t abstract, it’s personal.