“I’ve lost track of all time, hours, days,” says Mehdi Hasan, explaining it has been “a manic six weeks.”

The former MSNBC host launched his own media company, Zeteo, on April 15, and things are hectic — in a good way. After Hasan raised $4 million in seed money, Zeteo generated more than 20,000 paid subscribers in its first two weeks. While a standard subscription costs $8 per month, or $72 per year, many subscribers have paid a whole lot more.

“I’m not going to tell you how many founding members we have, who paid $500,” Hasan says, but he adds: “We offered a signed copy of my book, a personalized signed copy, to founding members — that was our offer at the beginning — thinking there’d be like, I don’t know, 50-100. We’ve had so many founding members, we had to take that offer off because I simply can’t sign so many books.”

“I left MSNBC and a lot of people seem to have come with me,” he adds.

More importantly, when he spoke with Rolling Stone last week, Hasan noted his website was already making its presence felt. After Zeteo published a column from a Jewish Ph. D. student at Columbia University defending its pro-Palestine protest encampment, a CNN anchor read a portion of the commentary to House Speaker Mike Johnson (R-La.) and asked him to respond to it.

“We got the House speaker responding to an op-ed live on CNN primetime,” says Hasan.

For Hasan, this is effectively proof of concept: “The reason I wanted to set up Zeteo and not just go be a freelance journalist and actually build something,” he says, “is because on the progressive end of that media spectrum … there isn’t enough variety. There aren’t enough credible organizations. There aren’t enough organizations that actually have an impact.”

The Mehdi Hasan Show on MSNBC was canceled in November, less than two months after Hamas’ Oct. 7 attack and the start of Israel’s brutal war in Gaza. News of the show’s end prompted significant outcry. Hasan, one the most prominent Muslim journalists in American media, had been a vocal critic of the Israeli war, and he was known as one of the furthest-left voices at MSNBC. He left the network after his last show in January, and recently told New York Magazine, “I signed an exit agreement with mutually agreed terms to leave.”

Now, he gets to pick exactly what to cover, without outside pressure. Indeed, Hasan says he wants Zeteo’s coverage focused almost exclusively right now on “genocide in the Middle East.”

In the nearly seven months since Israel launched its war in Gaza, more than 34,000 Palestinians have been killed, millions have been displaced, and half the population is at imminent risk of famine. Hasan says the media, broadly-speaking, has covered the war and pro-Palestine protests “horrifically badly.”

“I think history will judge those of us who had platforms in this moment in time, and used those platforms to either ignore the plight of the Palestinians, dehumanize Palestinian children, who are literally starving to death, and instead … [used] our media platforms, our Twitter accounts, and primetime shows to create a moral panic about Jewish, Arab American, and white atheist protesters on college campuses,” says Hasan.

To launch his business, Hasan turned to an increasingly popular path for journalists going independent — relying on reader funding, building an email list, and hosting the company on the subscription platform Substack.

“For me, the business model is less about how do you make lots of money, and more about what is sustainable? What actually helps you do progressive journalism?” says Hasan. He adds that he didn’t want to “be at the whims of advertisers or tech bosses” like Facebook’s Mark Zuckerberg or Elon Musk, who owns X. “It means I don’t have to worry about shadow-banning or the corporate advertisers not liking my coverage on whatever it is — probably Gaza.”

Hasan notes his MSNBC clips often went viral, including among people who “don’t normally pay attention to progressive journalists.” And he’s proud of managing to platform people who wouldn’t typically be invited on the cable news channel.

“Noam Chomsky once emailed me saying Mehdi, you’re the only person in 25 years who invited me on at MSNBC,” he says, referring to the renowned professor and left-wing media critic. “I’ll take that to my grave. If I achieved nothing else in journalism, I got Noam Chomsky on MSNBC — not once but twice.”

The second story Hasan wants Zeteo focused on is “the fascist threat at home” posed by a potential second term in office for former President Donald Trump.

Hasan points out that Trump has suggested at his rallies that reporters should be imprisoned, raped, and tortured, so that they give up confidential information about their sources.

“No politician in the West has ever said that — Trump said it,” says Hasan. “This is the guy who we’ve normalized, who we treat as you know, just fatalistically as our next president … The complacency of the American people and American political media elites is something that will forever baffle me. And I’ll be baffled about it while I’m sitting in a detention camp in 2027.”

He questions whether, if Trump wins, the United States will continue to hold elections. In that vein, he worries that President Joe Biden’s ongoing support for Israel’s war in Gaza will cost him the election and ultimately “sacrifice the future of American democracy.”

He adds, though: “It’s April right now. As we’re speaking, people are being killed in Gaza. Right now, the only thing that matters is pressuring Biden and the Democrats to do the right thing.”

Surveying the media landscape today, Hasan says, “So much is missing that Zeteo cannot plug that massive, gaping hole in our media coverage — whether it’s college campuses, whether it’s Trump vs. Biden, whether it’s issues like poverty and inequality, whether it’s the Middle East and Gaza — there are a lot of holes, there’s a lot missing. We’re trying to do our best.”

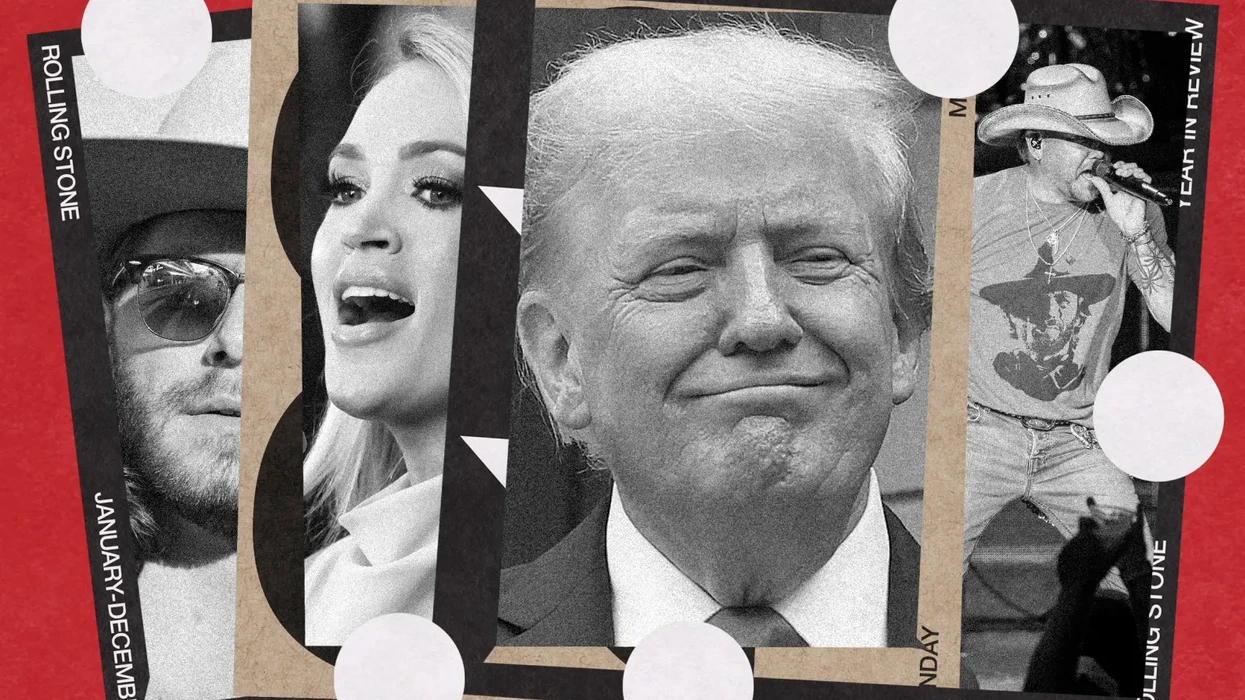

President Donald Trump discussing Venezuela at a press conference at Mar-a-Lago.

Why Venezuela Could Be a Turning Point in Gen Z’s Support for Trump

When Donald Trump called himself “the peace president” during his 2024 campaign, it was not just a slogan that my fellow Gen Z men and I took seriously, but also a promise we took personally. For a generation raised in the shadow of endless wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, it felt reassuring. It told us there was a new Republican Party that had learned from its failures and wouldn’t ask our generation to fight another war for regime change. That belief stood strong until the U.S. overthrew Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro.

Growing up in the long wake of the wars in Iraq in Afghanistan shaped how my generation learned to see Republicans. For us, “traditional” Republican foreign policy became synonymous with unnecessary conflicts that caused young people to bear the consequences. We heard how Iraq was sold to the public as a necessary war to destroy weapons of mass destruction, only to become a long conflict that defined the early adulthood of many millennials. Many of us grew up watching older siblings come home from deployments changed, and hearing teachers and coaches talk about friends who never fully came back. By the time we were old enough to pay attention, distrust of Bush-era Republicans wasn’t ideological, it was inherited from what we had heard.

As the 2024 election was rolling around, that dynamic had flipped. After watching wars in Ukraine and Gaza dominate headlines while Joe Biden was president, the Democrats were now the warmongers. My friends constantly told me how a vote for Kamala Harris was a vote to go to war. On the other hand, Donald Trump and the Republicans were the ones my friends thought could keep us safe. “I’m not voting for Trump because I love him,” one friend told me. “I’m voting for him because he cares about us and I don’t want to go fight in a stupid war.” For many of my friends, much of their vote came down to one question: Who was less likely to send us to fight? The answer to them was pretty clear.

Fast forward to now, and Venezuela has begun to complicate that belief. Even without talk of a draft or a formal declaration of war, the renewed focus on U.S. involvement and troops on the ground has brought back the same language of escalation my generation was taught to distrust. Young men online have been voicing the same worries, concerned that the ousting of Maduro mirrors the early stages of wars they were raised to fear. When I asked a friend what he thought about Venezuela, he shared that same sentiment. “This is how all these wars always start,” he told me. “They might try to make it sound like it’s not actually a war, but people our age always end up being the ones that pay the price for it.” For young men who supported Trump because they believed he represented a break from interventionist politics, Venezuela blurs the line between the “new” Republican Party they thought they were backing and the old one they were raised to reject.

For many young men, Venezuela has become a major part of a broader shift of how they view Trump. A recent poll from Speaking with American Men (SAM) found that Trump’s approval rating has fallen 10 percent among young men, with only 27 percent agreeing with the statement that Trump is “delivering for you”.

Gen Z men’s support of Trump was never about ideology or party loyalty, it was about the idea that he had their back and would fight for them. But that’s no longer the case. Recently, Trump proposed adding $500 billion to the military budget. Ideas like that will only hurt the president with young men. My friends don’t want more military spending that could get us entangled in foreign wars; they want a president who keeps them home and fights for their economic and social needs. As Trump pushes for a bigger military and more intervention abroad, the promise that once made him feel like a protector of young men now feels out of reach.

For my generation, Venezuela isn’t just another foreign policy dispute, it’s a conflict many young men worry they could be the ones sent to fight. Gen Z men didn’t support Trump because he was a Republican, but because they believed he was different from the old Republicans. He would be a president who would have their back, fight for their interests and keep them from fighting unnecessary wars. Now, that promise feels fragile, and the fear of being the ones asked to face the consequences has returned. For a generation raised on the effects of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, the idea of another war isn’t abstract, it’s personal.