A MAGA congressman from Arizona is comparing GOP poll watchers being trained by the Trump campaign to SEAL Team 6 snipers, insisting that these “boots on the ground” must be prepared to counter a “desperate” opposition that will “do whatever it takes to hold on to power.”

The congressman, Eli Crane, represents a large swath of northern Arizona. He is a Navy veteran who was deployed with the SEALs, and later created a business selling bottle openers fashioned out of giant 50-caliber rifle shells, a company that was featured on Shark Tank.

A first term congressman, Crane is a member of the extreme-right Freedom Caucus, and was one of eight GOP members who precipitated the ouster of Kevin McCarthy as speaker of the House. He refers to Matt Gaetz as a “brother” and recently received Donald Trump’s “Complete and Total endorsement!”

Crane is also a conspiracy theorist. He is an avid election denier who has long refused to accept that Trump lost the 2020 election, claiming “massive amounts of fraud.” Crane has recently received national media attention for his baseless insinuation that the Trump assassination attempt may have been a plot orchestrated by “people in our government.” (Crane’s office did not immediately return a request for comment.)

Crane appeared on a July 28 video call organized by the Trump campaign to train volunteer “poll watchers”; video of the event was obtained exclusively by Rolling Stone. The Trump campaign is attempting to mobilize 100,000 MAGA volunteers to monitor polling locations around the country, supposedly to document irregularities.

Poll watching can be a routine part of a fair election. But it also has a dark history of crossing into voter intimidation. In Mesa, Arizona, in 2022, for example, masked vigilante poll watchers staked out ballot drop boxes, wearing tactical gear and toting guns. Marc Elias, a top Democratic elections lawyer, has warned that the Trump campaign is seeking to create a “massive voter suppression operation.”

The call was part of a “National Day of Election Integrity Virtual Training” organized by the Republican National Committee and attended by Trump campaign Arizona officials as well as dozens of MAGA activists. Crane touted the call as part of taking back “our country from the Radical Left!”

Far from attempting to lower the temperature of the political debate, Crane used incendiary language from the jump, warning the audience that “our opposition” would do “whatever it takes to hold on to power.” Crane pointed conspiratorially to the recent “assassination attempt on our president” as a sign of “just how desperate the opposition is becoming.”

The congressman spoke to the poll watcher trainees as if they were military recruits, calling them the new “boots on the ground.” Crane insisted the Trump campaign’s election integrity effort “reminds me so much of my old job when I was in Special Forces, in the SEAL teams,” citing the teamwork required.

“We had snipers. We had breachers,” Crane, said while also highlighting the behind-the-scenes support of communications technicians and surveillance drone pilots. “If everybody else didn’t do their job, you wouldn’t get to the proper target,” he said. “You wouldn’t be able to hit it.”

Crane recalled that the stakes of such teamwork — “many different people with so many different skill sets, all contributing toward the same mission” — were life and death, and that failure meant “you wouldn’t be able to come home to your family.” Crane then declared, bizarrely, of the work of monitoring polling sites in November: “This is the same thing.”

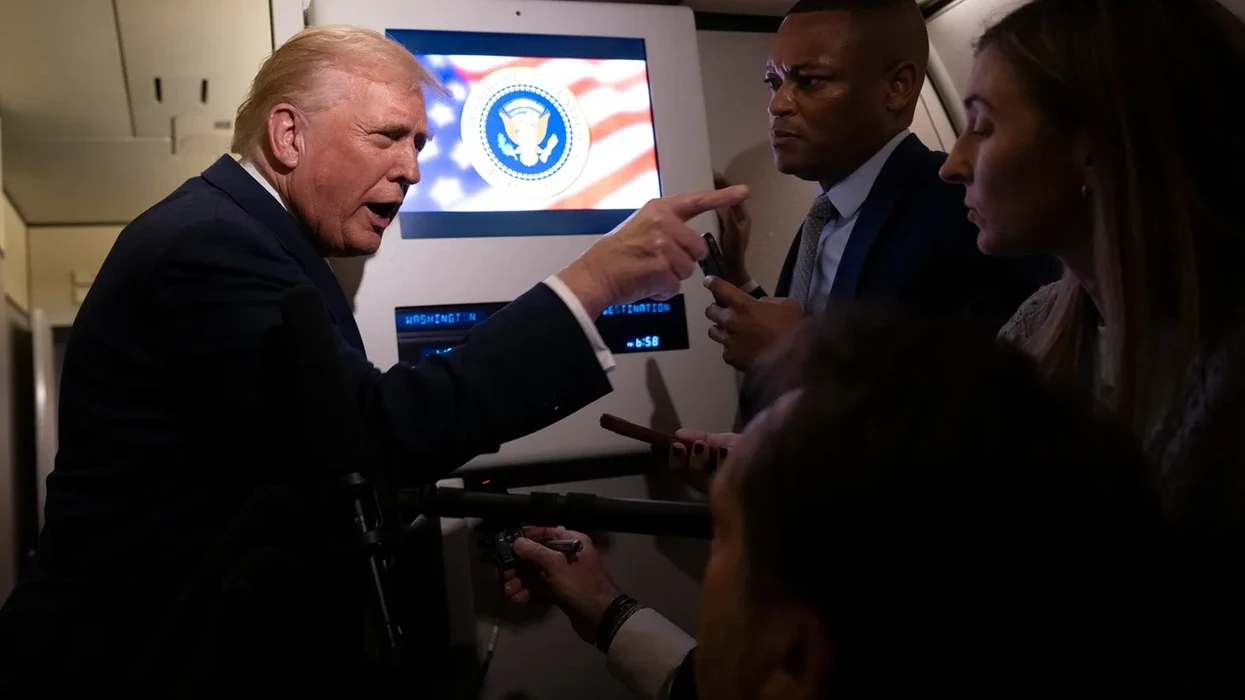

President Donald Trump discussing Venezuela at a press conference at Mar-a-Lago.

Why Venezuela Could Be a Turning Point in Gen Z’s Support for Trump

When Donald Trump called himself “the peace president” during his 2024 campaign, it was not just a slogan that my fellow Gen Z men and I took seriously, but also a promise we took personally. For a generation raised in the shadow of endless wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, it felt reassuring. It told us there was a new Republican Party that had learned from its failures and wouldn’t ask our generation to fight another war for regime change. That belief stood strong until the U.S. overthrew Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro.

Growing up in the long wake of the wars in Iraq in Afghanistan shaped how my generation learned to see Republicans. For us, “traditional” Republican foreign policy became synonymous with unnecessary conflicts that caused young people to bear the consequences. We heard how Iraq was sold to the public as a necessary war to destroy weapons of mass destruction, only to become a long conflict that defined the early adulthood of many millennials. Many of us grew up watching older siblings come home from deployments changed, and hearing teachers and coaches talk about friends who never fully came back. By the time we were old enough to pay attention, distrust of Bush-era Republicans wasn’t ideological, it was inherited from what we had heard.

As the 2024 election was rolling around, that dynamic had flipped. After watching wars in Ukraine and Gaza dominate headlines while Joe Biden was president, the Democrats were now the warmongers. My friends constantly told me how a vote for Kamala Harris was a vote to go to war. On the other hand, Donald Trump and the Republicans were the ones my friends thought could keep us safe. “I’m not voting for Trump because I love him,” one friend told me. “I’m voting for him because he cares about us and I don’t want to go fight in a stupid war.” For many of my friends, much of their vote came down to one question: Who was less likely to send us to fight? The answer to them was pretty clear.

Fast forward to now, and Venezuela has begun to complicate that belief. Even without talk of a draft or a formal declaration of war, the renewed focus on U.S. involvement and troops on the ground has brought back the same language of escalation my generation was taught to distrust. Young men online have been voicing the same worries, concerned that the ousting of Maduro mirrors the early stages of wars they were raised to fear. When I asked a friend what he thought about Venezuela, he shared that same sentiment. “This is how all these wars always start,” he told me. “They might try to make it sound like it’s not actually a war, but people our age always end up being the ones that pay the price for it.” For young men who supported Trump because they believed he represented a break from interventionist politics, Venezuela blurs the line between the “new” Republican Party they thought they were backing and the old one they were raised to reject.

For many young men, Venezuela has become a major part of a broader shift of how they view Trump. A recent poll from Speaking with American Men (SAM) found that Trump’s approval rating has fallen 10 percent among young men, with only 27 percent agreeing with the statement that Trump is “delivering for you”.

Gen Z men’s support of Trump was never about ideology or party loyalty, it was about the idea that he had their back and would fight for them. But that’s no longer the case. Recently, Trump proposed adding $500 billion to the military budget. Ideas like that will only hurt the president with young men. My friends don’t want more military spending that could get us entangled in foreign wars; they want a president who keeps them home and fights for their economic and social needs. As Trump pushes for a bigger military and more intervention abroad, the promise that once made him feel like a protector of young men now feels out of reach.

For my generation, Venezuela isn’t just another foreign policy dispute, it’s a conflict many young men worry they could be the ones sent to fight. Gen Z men didn’t support Trump because he was a Republican, but because they believed he was different from the old Republicans. He would be a president who would have their back, fight for their interests and keep them from fighting unnecessary wars. Now, that promise feels fragile, and the fear of being the ones asked to face the consequences has returned. For a generation raised on the effects of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, the idea of another war isn’t abstract, it’s personal.