During the last period of his time as president, while the Watergate scandal was raging, Richard Nixon allegedly told several U.S. representatives that he could get on the telephone, issue an order, and soon after millions of people would be killed. It wasn’t hyperbole. There are very few people in human history that have ever had that kind of power, and most have been American presidents. But how does one individual with this sort of authority exist in a system of government designed with a triad of co-equal branches set up specifically to thwart concentrated executive power, a system where starting a war wasn’t even an executive-branch power in the constitutional design?

The question of what in our system could have prevented Nixon from causing a nuclear holocaust if he wanted to has been left unanswered. There have been rumors that Cabinet secretaries at the time were telling aides to ignore such a presidential order if it were issued, but that’s a stop-gap measure, not a constitutional check. The designers of our republican system never intended their chief executive to have this sort of authority. The fact that presidents do today is the root cause of many of our national problems.

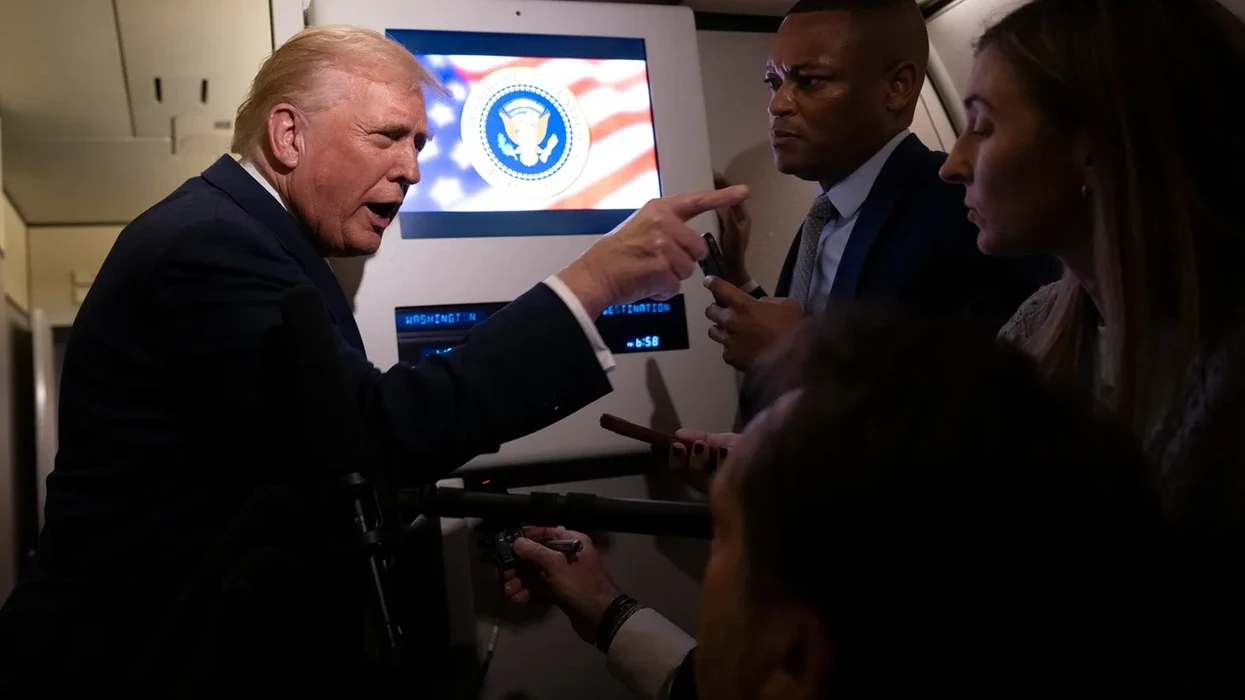

Americans are living though a historic moment right now, one that would be fascinating to watch were it not so insanely important. There is a disaster looming that is becoming more clear every day. The cause is that the office of the president of the United States has far too much power and very few constraints. This combination invites authoritarianism. All it needs to become manifest is someone in the White House who desires such an outcome. It seems we have someone like that now.

While it’s both tempting and normal to see current conditions as the result of recent events, the 21st-century American political situation is the culmination of decades of trends involving the ever-increasing power of the presidency. None of this is hidden, and scholars have been writing about it for decades (Arthur Schlesinger Jr.’s famous book The Imperial Presidency was published in 1973). And while the aggregation of presidential power is often cloaked in rationales and justifications, from anti-communism to anti-drugs, war powers, anti-terrorism, et cetera, sometimes it’s simply how things developed and evolved (the nature and challenges associated with nuclear weapons is an example). But there is no denying at this point that we have created a systemic monster that the constitutional framers wouldn’t recognize — and one they would fear. The founders believed in diffused power and oversight. They believed in a strong and active legislative branch to counter autocratic mission creep. We have none of those things at the moment. Are any of them recoverable? Is constitutional erosion a one-way street, or can it be reversed with some sort of renaissance? Must we go the way of Rome’s Republic?

To rebalance our constitutional portfolio first requires us to want a less powerful executive. This is somewhat counterintuitive. Americans are accustomed to electing leaders who promise to push for outcomes, foster positive change, fix things, and help people. The voters expect the president to use the power of the office to achieve what the people want. The pressure from the winning candidate’s supporters is not to restrain power but to use as much of it as possible. We are addicted to the exercise of presidential authority as long as it is being used for ends we desire. The effect this has on the system as a whole is given little attention. Is it even conceivable that we might push for leaders to restrain or roll back whatever power they might claim in order to prevent us from getting a president with too much authority? What if that’s the only way to repair things?

If we come out of this current inflection point constitutionally intact — and that’s far from guaranteed — we should use any pendulum-swinging momentum for reform the way legislators used the Watergate scandal aftermath to try to rein in the runaway powers of the presidency. There were lots of hearings, investigations, and legal alterations done in the mid-1970s to “fix” things, along with punishments meted out to those in government who knowingly went too far. This seems healthy for any system when its constitutional flaws are exposed. But like a noxious weed, the growth of executive power returned with a vengeance starting in the 1980s. Many of the post-Watergate reforms were challenged, overruled, or functionally eviscerated. The rationale given was that the “legitimate” powers of the presidency had been encroached upon. The formerly fringe concept of the Unitary Executive Theory emerged as a justification for unilateral actions and presidential power consolidation, pushed by think tanks (and the Supreme Court justices they pushed for) and entities who wanted less interference from other branches of government. This is the same rationale Donald Trump and his surrogates cite continually.

Any effort to dial back presidential authority faces strong headwinds in our current political climate. The Supreme Court seems hell-bent on ceding ever more power to the president, one who has far more power now than the “imperial” Nixon did back in the early 1970s. The electorate has demonstrated that it’s willing to support chief executives pushing constitutional boundaries if it’s done for reasons voters favor. And neither party wants to unilaterally disarm by ceding authority if the other side can’t be trusted to do the same. Any salvation coming from the legislative branch seems hopeless. This dynamic is decades in the making; Congress has grown weak, venal, co-opted, and seems happy to relinquish its power to avoid responsibility for anything that might hurt members’ reelections. Frustration with Congress leads to even more temptation to use presidents to achieve political goals — often using executive orders — that lawmakers seem unable or unwilling to pursue. The dynamic isn’t favorable.

But we have been given another reminder of why any of those good reasons for increasing the power of one human being at the expense of the rest of the government aren’t good enough. The executive branch is the one overwhelmingly likely to bring us to a dictatorship, and we can now see how much the vast powers of the office have only been held in check by mere protocol. A president unleashed shows us the power of the modern office uncloaked. And it should scare us all back into the mindset of Ben Franklin when he said that we had “a republic, if you can keep it.” Congress, with its many members, isn’t likely to be the branch that takes democracy away from us. The danger comes from the executive branch where one person calls the shots. And as it was when Nixon fell, we are being reminded that increasingly powerful presidents are something the system seems to germinate naturally. We need to periodically prune back the executive’s powers when the opportunity presents itself. That time must be soon. The weeds have overrun the garden.

Too many forget that the primary goal of the U.S. constitutional design wasn’t efficient governing. It was tyrant prevention. We put up with all sorts of impediments to change, reform, and improvement for that one simple goal. Whether this firewall still works is the paramount political question of our age. Will this era turn out to be a blip on the timeline? A warning that prompts reflection, reform, and recalibration akin to the McCarthyistic “Red Scare” era? Or will it be a Caesar crossing the Rubicon moment that forever ends the American experiment?

The more scary aspect of all this is the degree of public support for an uber-powerful leader who champions their views and pushes for what they desire. Often these wishes are unachievable because our constitutional protections stand in the way. This is a problem that will outlive the current president and requires deep national introspection. We could start by reminding ourselves what happens when representative systems go sideways. The outcomes are not recalled fondly by those who lived through them. Better to acquire that lesson from some other nation’s tragedy rather than having to learn about the danger of historical hot stoves by touching one ourselves.

We are currently seeing what can happen when the only branch controlled by a single individual decides it wants to flex its vast and awesome powers. It demonstrates to all reasonable people that it’s too much power for one person to have. Imagining such authority in the hands of one’s worst enemy should be enough to make this concern clear to anyone. The president can pick up the phone and order the deaths of billions and the ruination of the planet’s ecosystem. That’s clearly too much power for any human being, isn’t it?

Sunsara Taylor (right, with Michelle Xai) is a leader and co-founder of Refuse Fascism.Juliana Yamada/Los Angeles Times/Getty Images

Sunsara Taylor (right, with Michelle Xai) is a leader and co-founder of Refuse Fascism.Juliana Yamada/Los Angeles Times/Getty Images Bob Avakian (pictured in 2014), who founded the Revolutionary Communist Party, has ties to Refuse Racism.Courtesy of The Bob Avakian Institute

Bob Avakian (pictured in 2014), who founded the Revolutionary Communist Party, has ties to Refuse Racism.Courtesy of The Bob Avakian Institute Members of the Revolutionary Communist Party march from the South End to Boston Common during May Day in Boston, May 1, 1980.Tom Landers/The Boston Globe/Getty Images

Members of the Revolutionary Communist Party march from the South End to Boston Common during May Day in Boston, May 1, 1980.Tom Landers/The Boston Globe/Getty Images Activists with RevComs held the protest near MacArthur Park in December 2024 ahead of President-elect Trump’s planned wave of migrant deportations.Mario Tama/Getty Images

Activists with RevComs held the protest near MacArthur Park in December 2024 ahead of President-elect Trump’s planned wave of migrant deportations.Mario Tama/Getty Images Refuse Fascism protestors hold a rally around the Washington Monument on November 5, 2025.Celal Gunes/Anadolu/Getty Images

Refuse Fascism protestors hold a rally around the Washington Monument on November 5, 2025.Celal Gunes/Anadolu/Getty Images

We Are Witnessing the Imperial Presidency on Steroids

The founders wouldn’t recognize the executive branch’s monstrous powers — but they sure would fear them