Donald Trump is privately trashing South Dakota’s MAGA Gov. Kristi Noem for executing her puppy and writing about it in her forthcoming memoir — a matter that appears to have closed the book on the idea of selecting her as a vice presidential nominee.

During conversations with close political allies and other confidants, sources say, the former president has repeatedly brought up the incident, including as recently as in the past couple days, to criticize Noem and question her political acumen.

This reporting is based on four sources familiar with the matter, and another two people briefed on it. Over the last few days, all but one source on this story approached Rolling Stone unprompted to describe recent discussions with Trump, or brought up the topic unsolicited during unrelated conversations.

Some of the sources candidly said they were disclosing these private details because they want Noem permanently eliminated from Trump’s 2024 vice presidential shortlist, or because they despise Corey Lewandowski, Trump’s former 2016 campaign chief who has advised Noem for years. Some separately said they were discussing this simply because Trump had been talking about Noem’s puppy slaying so frequently that it was, in the words of one of the sources, “getting kind of ridiculous” how “disgusted” the former president sounded about this and how much he has been “taunting” Noem behind her back.

Last week, The Guardian reported that Noem wrote in her new book about how she took her 14-month-old puppy, Cricket — a dog she “hated” — to a gravel pit and executed her, after the hunting dog displayed unruly behavior, including harming some of her neighbor’s chickens. The memoir, No Going Back, is set for release next week, with a blurb from Trump calling Noem a “tremendous leader” and her book “a winner.”

In recent days, the former president has discussed or brought up Noem’s pup-execution in closed-door meetings, as well as over the phone. Trump, sources recount, has pointedly asked questions regarding her decision to kill the dog, including specifically, “Why would she do that?” and “What is wrong with her?” He has expressed bewilderment that she would have ever admitted to doing this, willingly and in her own writing, and has argued it demonstrates she has a poor grasp of “public relations.” In these various conversations over the past week, the ex-president has also mentioned that voters generally don’t like politicians who kill dogs, two of the people familiar with the matter add.

Among the upper crust of MAGAland, Noem has long been considered a contender for Trump’s 2024 veep pick, though she was often viewed as a longshot. Those hopes appear to be dead now, after longtime allies and other conservatives close to Trump actively worked to place news stories about Noem and the dog in front of him, as Rolling Stone reported earlier this week.

Noem defended executing Cricket in an appearance on Fox News on Wednesday, telling host and informal Trump adviser Sean Hannity that the 14-month-old canine “was a working dog and it was not a puppy.”

“The reason it’s in the book is because this book is filled with tough, challenging decisions that I had to make throughout my life,” she added.

Noem was previously scheduled to headline a fundraiser on Saturday for Jefferson County Republicans in Lakewood, Colorado. The event was canceled due to apparent “safety concerns.”

The group wrote that “we were excited to have [Noem] speak at our annual fundraiser,” adding, “The timing was perfect, as it was just prior to her new book being released. We had no prior knowledge of the contents of the book when we invited her.”

As a result of “mainstream media coverage” about the book, the group said it has received death threats and its event was set to face protests. “Please know that the Jefferson County Republican Party is not taking a position on the public outcry on the governor’s book,” the group wrote.

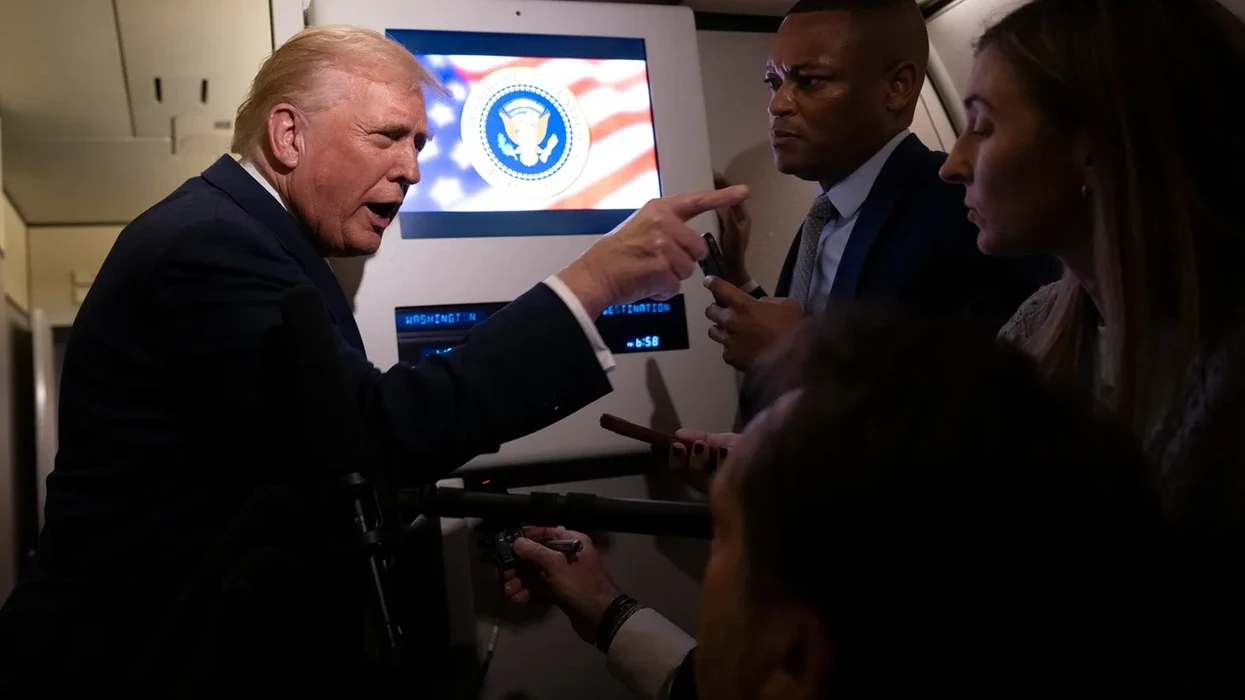

President Donald Trump discussing Venezuela at a press conference at Mar-a-Lago.

Why Venezuela Could Be a Turning Point in Gen Z’s Support for Trump

When Donald Trump called himself “the peace president” during his 2024 campaign, it was not just a slogan that my fellow Gen Z men and I took seriously, but also a promise we took personally. For a generation raised in the shadow of endless wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, it felt reassuring. It told us there was a new Republican Party that had learned from its failures and wouldn’t ask our generation to fight another war for regime change. That belief stood strong until the U.S. overthrew Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro.

Growing up in the long wake of the wars in Iraq in Afghanistan shaped how my generation learned to see Republicans. For us, “traditional” Republican foreign policy became synonymous with unnecessary conflicts that caused young people to bear the consequences. We heard how Iraq was sold to the public as a necessary war to destroy weapons of mass destruction, only to become a long conflict that defined the early adulthood of many millennials. Many of us grew up watching older siblings come home from deployments changed, and hearing teachers and coaches talk about friends who never fully came back. By the time we were old enough to pay attention, distrust of Bush-era Republicans wasn’t ideological, it was inherited from what we had heard.

As the 2024 election was rolling around, that dynamic had flipped. After watching wars in Ukraine and Gaza dominate headlines while Joe Biden was president, the Democrats were now the warmongers. My friends constantly told me how a vote for Kamala Harris was a vote to go to war. On the other hand, Donald Trump and the Republicans were the ones my friends thought could keep us safe. “I’m not voting for Trump because I love him,” one friend told me. “I’m voting for him because he cares about us and I don’t want to go fight in a stupid war.” For many of my friends, much of their vote came down to one question: Who was less likely to send us to fight? The answer to them was pretty clear.

Fast forward to now, and Venezuela has begun to complicate that belief. Even without talk of a draft or a formal declaration of war, the renewed focus on U.S. involvement and troops on the ground has brought back the same language of escalation my generation was taught to distrust. Young men online have been voicing the same worries, concerned that the ousting of Maduro mirrors the early stages of wars they were raised to fear. When I asked a friend what he thought about Venezuela, he shared that same sentiment. “This is how all these wars always start,” he told me. “They might try to make it sound like it’s not actually a war, but people our age always end up being the ones that pay the price for it.” For young men who supported Trump because they believed he represented a break from interventionist politics, Venezuela blurs the line between the “new” Republican Party they thought they were backing and the old one they were raised to reject.

For many young men, Venezuela has become a major part of a broader shift of how they view Trump. A recent poll from Speaking with American Men (SAM) found that Trump’s approval rating has fallen 10 percent among young men, with only 27 percent agreeing with the statement that Trump is “delivering for you”.

Gen Z men’s support of Trump was never about ideology or party loyalty, it was about the idea that he had their back and would fight for them. But that’s no longer the case. Recently, Trump proposed adding $500 billion to the military budget. Ideas like that will only hurt the president with young men. My friends don’t want more military spending that could get us entangled in foreign wars; they want a president who keeps them home and fights for their economic and social needs. As Trump pushes for a bigger military and more intervention abroad, the promise that once made him feel like a protector of young men now feels out of reach.

For my generation, Venezuela isn’t just another foreign policy dispute, it’s a conflict many young men worry they could be the ones sent to fight. Gen Z men didn’t support Trump because he was a Republican, but because they believed he was different from the old Republicans. He would be a president who would have their back, fight for their interests and keep them from fighting unnecessary wars. Now, that promise feels fragile, and the fear of being the ones asked to face the consequences has returned. For a generation raised on the effects of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, the idea of another war isn’t abstract, it’s personal.