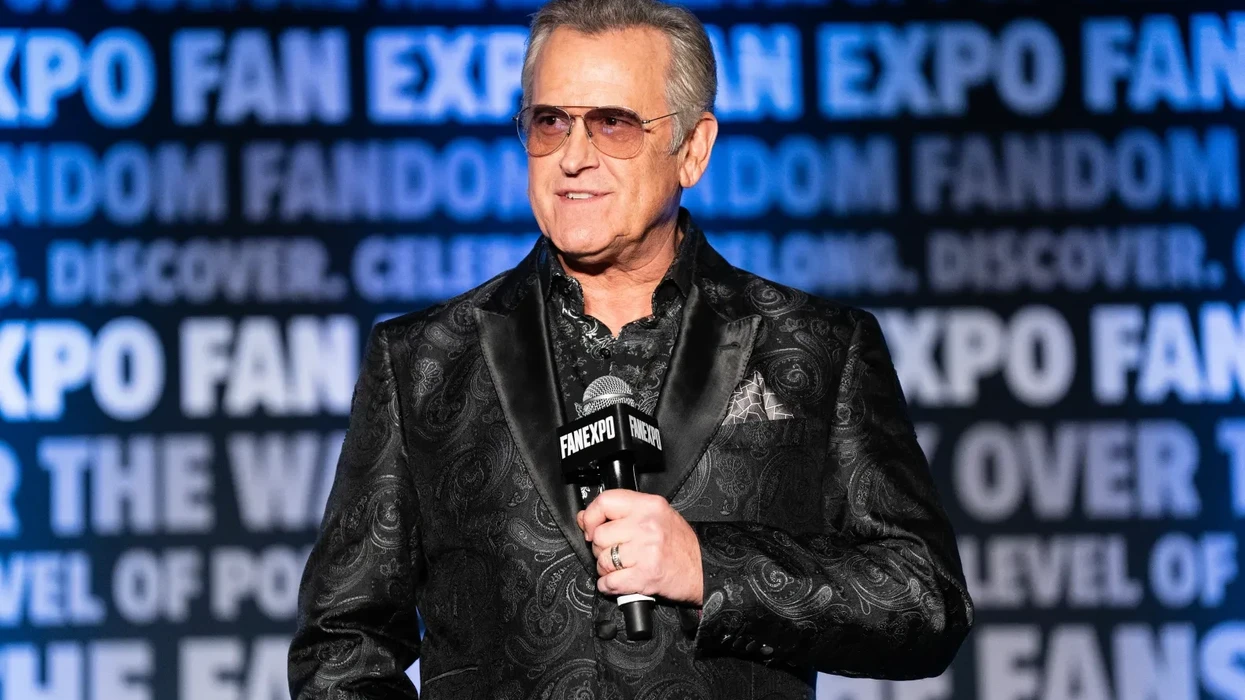

Tom Cochrane is a name that resonates in the history of Canadian rock. For several generations, he’s embodied both the raw energy of Red Rider’s early years and the powerful emotion of his solo career. Just mentioning Lunatic Fringe or Life is a Highway instantly brings fans’ collective memory back to those moments when music seemed capable of changing everything. Cochrane’s sensitivity as a songwriter and discipline as a seasoned live performer, have earned him eight Juno Awards, the Order of Canada, and an induction into the Canadian Music Hall of Fame.

His journey—and that of Red Rider—is marked by determination and a distinctly Canadian spirit. From their first shows in bars across Eastern Canada, the band learned to navigate a sometimes hostile environment. “I remember a show in Québec where the owner sabotaged our concert by unplugging the amps while we were playing. At the end of the week, he put a gun on the table when we asked for our pay,” Cochrane recalls. These formative experiences taught him resilience and resourcefulness, qualities that would prove useful throughout his career.

Red Rider quickly attracted attention with albums like Don’t Fight It in 1979 and As Far As Siam in 1981. The release of the single Lunatic Fringe marked a turning point. Suddenly, the band carried a weight that changed how audiences and fellow musicians perceived them. Cochrane had written the song as an anti-racist statement, drawing on lessons from history and the determination not to repeat past atrocities. Rock crowds, who might have been hostile to an opening act, recognized the importance of the track. Some Canadian bands touring with hard rock groups at the time were pelted with objects, but Red Rider was spared. The song also earned the respect of other musicians.

It was on the road that Cochrane also learned the importance of showmanship and connecting with the audience. Touring with The J. Geils Band, he discovered the art of performance: spectacular entrances, crowd interaction, and highlighting the energy of a live show. “Peter Wolf was a showman, he put heart and soul into what he did,” he says. He also recalls a night when Wolf entered Red Rider’s dressing room before a Detroit concert with two bottles of champagne and immediately asked Cochrane to explain the meaning of Lunatic Fringe.

For nearly a decade, Cochrane and Red Rider dominated the Canadian rock scene, multiplying tours and album sales. Cochrane started a family and enjoyed what he called “moderate success.” As the lead singer and principal songwriter, Red Rider became Tom Cochrane & Red Rider in 1986, gently transitioning toward a solo career. Their final full album, Victory Day, was released in 1988, and the band continued touring. In 1991, Cochrane began working on a solo album, splitting time between Nashville and Ontario.

A trip to East Africa with World Vision profoundly changed his outlook on life and inspired new creativity. “I saw things that left scars on my mind. A dying woman, her daughter in her arms, looking at us as if to ask what we were doing there with our cameras,” he recalls, describing the post-traumatic impact. “I felt like I saw my own daughters in her eyes.” This intense experience fueled the creation of Mad Mad World, an album that would transform Cochrane’s career. One day in the studio, John Webster, the only member of Red Rider he brought into his solo career, suggested revisiting a song draft Cochrane had written for the band but never used.

Originally titled Love is a Highway, Cochrane took Webster’s suggestion and turned it into an international anthem. “You had to keep your eyes on the road ahead, because otherwise you risk crashing,” he explains, describing the song’s central metaphor. The final version, recorded in his home studio and produced with Joe Hardy in Memphis, combines thoughtful composition with lyrics that resonate universally.

The success of Life is a Highway was immediate. In Canada, sales skyrocketed and festivals followed. In the United States, the song climbed the charts, topping them for several weeks. “I went from comfortable success to being a pop star at 38. It was a very strange phenomenon,” Cochrane remembers. This meteoric rise was not without personal consequences: a tested marriage, family distance, and the constant pressure of touring.

Yet Cochrane always maintained a clear philosophy: nurturing a genuine connection with the audience. He recalls a concert at West Point, performing for cadets in military uniform, where the crowd remained still during the first part of the set. When Lunatic Fringe played, the reaction was immediate: “Hats were flying everywhere, they were screaming… it was incredible,” he says. This ability to move people and evoke strong emotions remains at the heart of his art.

Despite international success, Cochrane remains deeply connected to his Canadian roots. “Being Canadian is part of who I am. It gave me perspective, resilience, and a sense of community and culture, and it informed every note I played,” he emphasizes. Even in the 1970s and 1980s, when one often had to downplay their origins to succeed in the United States, he refused to deny his identity. This fidelity to his values is reflected in the consistency of his work and the respect he commands among peers.

He believes music has the power to touch people, provoke reflection, and inspire change. “Music can do more than entertain. It can illuminate and open hearts to what really matters,” he asserts.

Approaching the 35th anniversary of Mad Mad World, Cochrane continues to tour, write, and create. With a new album and some unreleased tracks in the works, he remains true to his mission and vision. “I wouldn’t trade this journey for anything.”

Songs You Need to Know

Songs You Need to Know