Search

Ne manquez rien

Un journalisme qui compte. Une musique qui inspire.

Most Popular

More Stories

Florence Welch: ‘Anxiety is the Hum of My Life — Until I Step Onstage’

Nov 12, 2025

If you talk to Florence Welch on any given day, it’s safe to assume she’s feeling a little anxious. “Anxiety is the constant hum of my life,” she says. “Then I step out onstage, and it goes away.”

Luckily, that’s where she is right now: draped in a long white dress, sitting comfortably in front of a 150-person audience at New York’s beautiful Cherry Lane Theatre, a storied downtown venue known as the birthplace of off-Broadway theater. It’s a week before the release of Everybody Scream, the excellent sixth album she made with her band, Florence + the Machine, and Welch is here for the first-ever live edition of the Rolling Stone Interview, the magazine’s long-running deep-dive conversation series. (The interview is also the first-ever video podcast version of the franchise — check it out on Rolling Stone’s YouTube channel and wherever you get your podcasts.)

During both the interview and a stripped-down, spellbinding performance, the energy in the room is as electric as the new album — even when the subject matter is not necessarily light. Made with collaborators like the National’s Aaron Dessner, Idles’ Mark Bowen, Mitski, and James Ford, Everybody Scream is a visceral and mystical reflection on life and loss, not to mention a showcase for Welch’s remarkable voice, which has proved to be one of the most powerful instruments in popular music since her band debuted in 2009. The songs were spurred by her experiences touring in support of 2022’s Dance Fever, where she suffered an ectopic pregnancy and ruptured fallopian tube that required life-saving emergency surgery.

Throughout the conversation, Welch balances a deep candor with a dry wit while analyzing the ways she’s evolved over the years, and what it’s meant for her music. “The calmer my life got, the wilder I could be in my performance styles and in my videos and in my artwork,” she surmises, midway through our talk. “I found that freedom from shame means that you can explore so many more different things in your work, and I really found that to be amazing.”

The story of this album starts with your last tour, for 2022’s Dance Fever. Can you tell me about going into that tour and how you left as a different person after it?

I guess in a way Dance Fever was a record of prophecy and this record is a record of catastrophe. [Dance Fever] dealt with performance as well, and the fact that all the performance had been taken away. There was a period when musicians really didn’t know if live music would come back, and it was a record questioning whether I wanted to keep doing it or whether I would want to start a family. And then on that tour, I had a life-and-death experience that then led me into making this record.

Everybody Scream came out of wanting to go deeper into magic and mysticism. Like, “OK, shit is coming true. I really need to figure out what’s fucking going on here.” It opened up a portal to another place. It was a place of real exploration, and it opened up all these different tendrils of myself going through something like that.

Have you ever had an album or song prophesize what came after?

It was never this literal. I wrote a song [for Dance Fever] called “King,” which was wrestling with whether I wanted to be a mother. There was a line in it that was like, “I never knew my killer would

be coming from within.” The thing that nearly killed me was a complication with a pregnancy loss onstage. It was never that

on the nose.

What brought you to study more magic and mysticism?

When something happens in the body, you feel so powerless. I think I was looking for forms of power and felt very primal. It was very sudden, very violent, [and] absolutely saved my life. When you have to have emergency surgery, the lights are so bright; it’s so clinical. There was a sense afterwards that I needed to be near to the earth. I needed to be near natural things.

Everywhere you look in terms of stories of birth and life and death, I found stories of witchcraft. You couldn’t look into anything about it and not find these folktales or find stories of witches or magic because it is so unknown. No one could tell me why this happened to me. They [told me] “just bad luck.” When no one can tell you why, you’re looking to find meaning. You’re looking to find a way to understand it, and also some kind of control.

You experienced pregnancy loss onstage, while performing in front of thousands of people. How did you navigate that as a performer?

I was in pain. And what do you do as a woman? I just took some ibuprofen [and] went to work. I was in a place that I understood. I was in a place of bodily power and control, and I was experiencing a loss. I didn’t know it was a dangerous loss, but I was like, “I’m going to get through this, and if I can get through this show, at least I haven’t lost another thing.” When I stepped out on that stage, all the pain just went away, and I was free. It was weirdly an incredible show because I didn’t know that I was dying in some way. I didn’t know I had internal bleeding by then. But I felt this kind of presence that’s always been with me onstage take over, and it carried me through the whole thing. It was like love or something. I was in the mud and in a hurricane, and weirdly, it was really beautiful. Does that sound fucked up to say?

Did you start working on or writing the album shortly after, or did it take some time to process?

I’d started making the album already. The first person I worked with was Mark Bowen of the band Idles. When we both had time off from tours, we would get together and start sketching things out. “One of the Greats” had already started to emerge, and then I think we wrote “Everybody Scream.” But, yes, I went straight from the tour to the studio. After everything that happened, there was this need to process it.

I had some trauma therapy afterwards. She was great. Obviously, it was a specialist for people who have gone through things that I went through. And she [said] there can be a need to really fix it immediately and to fix it by trying to have a kid again really quickly. She was like, “The only bit of advice I really can give you is don’t try again until you feel like yourself again.” The only [place] I really feel like myself is making songs, so that’s how I process things that happened.

I don't remember the first six months of making this record, really. Songs like “Witch Dance” and “You Can Have It All,” the first really raw ones that were written pretty immediately afterwards, I don't really remember. What was amazing about doing them with Bowen was he has so much discordance and this punk element to it with the brutality of some of his sounds. I needed that. It was brutal. What happened to me was a discordant event in my life. So it was sort of amazing that we'd already started working together. He was the perfect person to be writing songs like that in the aftermath of it.

There’s a great sense of humor on this album. On “Music by Men,” you sing: “Breaking my bones/Getting four out of five/Listening to a song by the 1975/I thought, ‘Fuck it, I might as well give music by men a try.’ ” Which song by the 1975 were you listening to at the time?

[Singing] “We’re fucking in a car/Shooting heroin/Saying controversial things …”

“Love It If We Made It”?

Yes! I was like, “This song is really good.” A big thing with songwriting is it’s often because it rhymes. So you needed a band that rhymed with “five.”

When I broke my foot onstage, I got four out of five stars for that show. I was like, “What more do

I have to do?” I literally bled all over the stage. People were mopping it up and I finished the fucking show, and I think across the board it was like, “Four out of five.” Fuck’s sake. What now?

On “One of the Greats,” you sing, “I’ll be up there with the man and the 10 other women and the 100 greatest records of all time/It must be nice to be a man and make boring music just because you can.”

A lot of the lines in there, I just found them really funny. It was this feeling of “When is it going to be good enough?” I give so much and sometimes I wonder if in that giving and in not having that almost masculine cool of holding stuff back, being obtuse, not saying it all like, “What is he saying? That’s

so cool. What do those lyrics mean?” … I was like, “If I keep giving this much, does that mean people aren’t taking me seriously?”

But then sometimes when I listen to things that have that level of masculine reserve, I'm just like, "Isn't this kind of boring though? What are they saying?” Maybe it would be an easier life to be able to hold things back, to be able to just be hot in a T-shirt and everyone be like, "Wow, it's revolutionary." I'm jealous. If you're insulting someone, it comes from envy, honestly.

Was it that same concert review or a different moment that spurred you to consider the limitations of how women are perceived in the industry?

You get all the lists, and there’s a sense that they have the amount of women they can fill and they’re like, “OK, we’ve ticked that box.”

If I’m being honest, I didn’t even really align with my gender, and I still don’t know what it fucking means to be a woman. I don’t know what that feels like. I don’t ascribe anything to it particularly.... So it meant that I didn’t really feel any barriers to me really because of it. You don’t realize until you get older, that people aren’t taking you seriously because you’re a young woman. I just thought it was because I was annoying. It’s only when you look back and see the same treatment happening over and over again to young women. You’re like, “Wait, I think maybe that wasn’t about me.”

And that does come with wisdom, but that also comes with fury. I think this record really wrestles with the extra sacrifices to commit to this life and to commit to the stage. I was speaking to Mitski about that, and she was like, “Yes, but the intimacy that that also brings you with performance, the intimacy that that brings you with work, is so extraordinary.” I feel that too.

Have you felt underappreciated or underrated as an artist?

It’s not a sense of being underrated. It’s just sometimes you’re looking at the wrong people to validate you. There’s all these people over here who love it and get it, and there’s just one dude who’s like, “Yeah, I’m not into it.” That is something that you grow out of, which is really nice. Also the way that I am appreciated is the only way I would have it. I never wanted to be any more famous than this. This is actually about as much as I can handle.

Eventually, through all the work, I got the career I always wanted. There was this moment where I think there would’ve been huge intentions for me to go very mainstream. On Lungs, there was

a moment where I could have chosen a different path. I don’t have the kind of brain that can handle that amount of attention. I kept making choices that took me away from the spotlight and always back to the work, or that took my personality out of it and always back to the music.

And when you step outside of all the trappings of being a rock star on stage and putting out an album, what does your life look like?

It's really boring. That's the thing, isn't it? Be calm in your life so you can be wild in your work. I think that was really true for me. The calmer my life got, the wilder I could be in my performance styles and in my videos and in my artwork. A lot of self-loathing and shame and everything, I was drinking or taking drugs to figure out. Once I got sober and my life became a lot quieter, I actually found that freedom from shame means that you can explore so many more different things in your work. I really found that to be amazing.

There’s a lot of pacing and reading and watching television. You're on tour and you're like, "I just need to get home." And then I get home, I'm like, "There is a beast inside me that needs to come out. I'm not meant for this life. I am too big for this house." The other bits of fame, I'm not really that interested in. I just find them stressful.

Like what?

There's a line in “Sympathy Magic” about “the vague humiliations of fame.” That's what I basically have found fame being like, just a series of small humiliations. The celebrity side of it has never really appealed. Because I'm shy or anxious and I need a lot of time to daydream, I need a lot of time out of the spotlight. I don't actually like a lot of attention. I don't like a lot of attention in general when it's not about my work. I think I like to lead a very private and quiet life off stage basically.

One of the first people that you called for this album was James Ford, who also worked on your breakthrough hit “Dog Days Are Over.” What do you recall of making a song that would end up changing your life?

I still have the CD with the original “Dog Days” demo on it. We were rehearsing at this studio called Premises Rehearsal Studios, which is still there in East London. [James] had his studio above Premises, and I went and knocked on his door. He says I came in and started banging on the table and singing it at him. The label that I'd been working with did not understand this demo whatsoever. They were just like, "No. Where's another 'Kiss With A Fist?' That was fun, cute, catchy guitars.” And James just understood it.

The first thing he did was he sped it up. It was a couple of BPMs slower. When I needed a lead single for this album, the demo that I had [for “Everybody Scream”] was really wild and quite a confusing song and he just completely understood it. But the first thing he did was sped it up. I was like, "Okay, I trust you. That went well the last time."

Have you had any mentors throughout your career?

Nick Cave has been so kind to me. Nick and Susie Cave have just been the most wonderful and kind friends. I sent Nick some of my poetry, and he helped me edit some. [I’d] write him stressed emails from tour, and he would reply and be so kind. As someone who's such a physical performer as well, he understood what I was putting myself through. He’s an incredibly wonderful human being.

You’ve been pretty selective with doing collaborations throughout your career, in terms of being a featured artist, but a big one you did do was “Florida!!!” with Taylor Swift. How did that come together?

She texted me being like, “I’d love to have you in this song.” The way she writes songs is like short stories. She had a whole story around this song, and why she wanted to write it, and the Florida lore. I wanted to bring what I knew of Florida, which is Lauren Groff. One of my favorite short-story collections is called Florida, and [Groff’s] from there. There’s a story in it called “Eyewall,” about a woman who barricades herself in a bathroom during a hurricane and is visited by all of the ghosts of her ex-boyfriends. And she’s drunk, and she’s holding a chicken. It’s an amazing, amazing short story.

Taylor was the most open collaborator. She was like, “Yes. Whatever you want. Do your backing vocals all over it. I want it to be as Florence-y as possible. Go for it.” I was like, “Well, I want to bang a drum, too.” And Taylor was like, “Yes, go for it.” Getting to watch her construct those harmonies that she does was an amazing experience.

On “One of the Greats,” you sing that you felt that you were “burned down at 36.” Do you still feel that way?

I actually think that when I turn 40, I’m going to feel amazing. I really do. It’s like when you are edging the decade, you start to feel worse and worse. So I think that when I turn 40, I’m going to feel incredibly young again. [There] was such a desperate urgency to this record and to get it out. If I hadn’t put this album out now, I don’t think that I would have ever put it out. It is so tied to this moment of the age I am, and the experiences that I’m having.

Had I had more time away from what happened, I would’ve felt differently about it. So I think I feel glad that I got to pull it together, just because it is such a silent and shadowy thing that so many suffer [from]. I was really sad at the idea of this album also not making it somehow. I’m glad that we managed to pull it all together.

Keep ReadingShow less

Featured Stories

Ne manquez rien

Un journalisme qui compte. Une musique qui inspire.

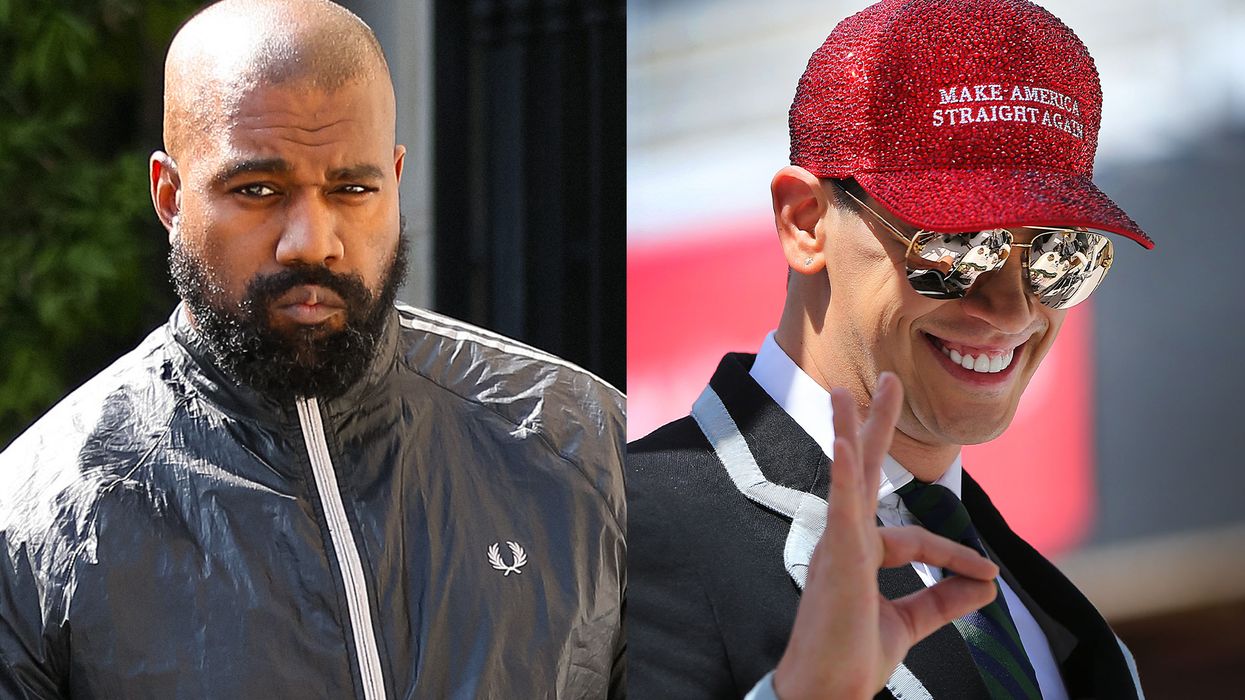

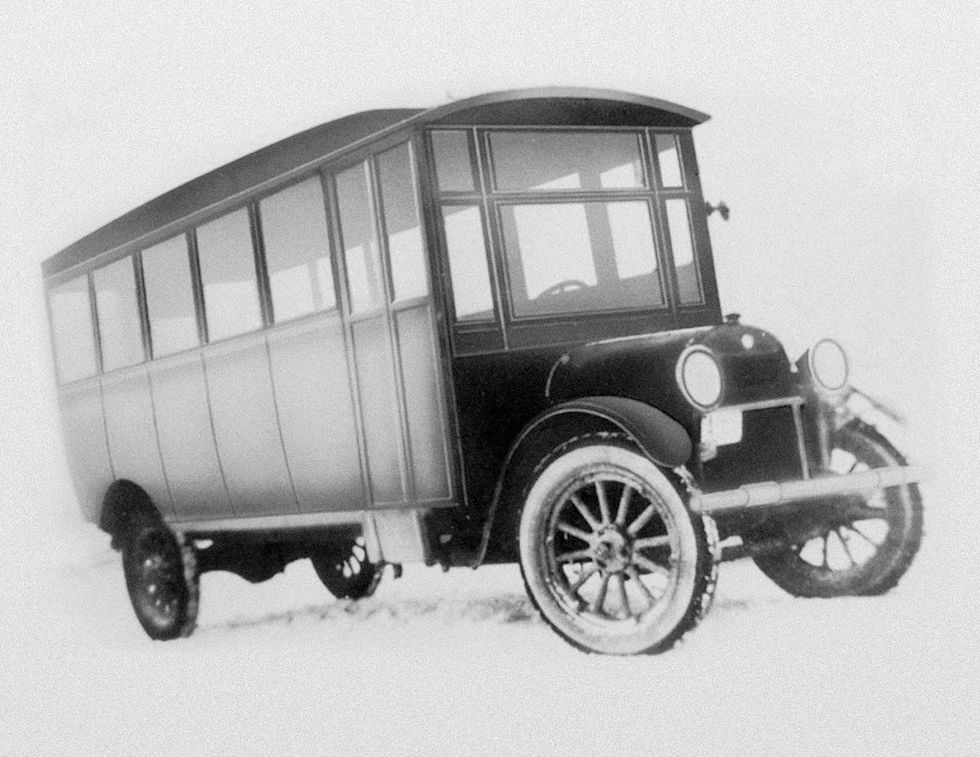

Prevost: the Québec company behind the biggest tours

Oct 20, 2025

If you’ve ever wandered backstage at a festival or through the private parking lot of an arena during a concert, you’ve probably noticed something: a long row of tour buses. And if you looked closely, you may have seen the same name on every single one: Prevost.

The story of these coaches, like that of nearly every tour bus in North America, doesn’t begin in Los Angeles but just outside Québec City.

That’s where I find myself on a rainy morning, the day after Def Leppard’s show at the Festival d’été, in Sainte-Claire, about thirty minutes from the city. From the moment you enter the village, you feel Prevost’s impact: a source of local and national pride and by far the region’s largest employer. The founder’s house still stands here, as do those of many of his descendants, including his grandson, Marco Prévost, who gives me a tour of the company’s massive factory.

The family dynasty, he explains, began when his ancestor Eugène Prévost, a cabinetmaker by trade, was hired to build the body of a REO truck that would transport villagers to the capital.

From War to World Tours

His skills quickly earned him a reputation, and orders started pouring in, but he limited production to one bus a year, since his main business at the time was building church pews. In 1939, he opened his first factory dedicated to bus manufacturing, which boosted output to ten vehicles per year. It came at the perfect time, as Prevost received a major contract from the Ministry of Defence during the Second World War.

Gradually becoming the continent’s leading coach manufacturer, Prevost began specializing in tour buses for artists in the 1980s and soon dominated the field entirely.

“Today, there are about 1,500 of our buses across North America, and we basically cover the entire entertainment industry since we’re the only player in that segment,” says François Tremblay, Prevost’s president.

Ingenious Québec Craftsmanship

What truly sets Prevost apart is the structure of its chassis, all built in Sainte-Claire. Normally, RVs and motorhomes are mounted on truck frames topped with fiberglass shells. “As you can imagine, over time, everything shifts and starts to go crooked,” Tremblay explains. Building on a stainless-steel bus chassis allows everything to stay perfectly aligned for decades. Even if a converter installs marble or tile flooring, “the floor will never crack.”

This durability translates into impressive numbers: Prevost coaches are designed to last an average of 20 years and often rack up more than 1.6 million kilometers over their lifetime. To ensure this, each bus undergoes rigorous testing in Sainte-Claire, including in a special chamber that simulates extreme weather to make sure they can withstand anything from a snowstorm in Thunder Bay to the California desert.

A Home on the Road

For touring professionals, driving comfort isn’t a luxury, it’s a survival requirement.

When I meet Laura Jean Clark in Québec City, she’s on tour with Slayer. “The bus becomes more of a home than my actual home,” she tells me. A tour manager for artists like Drake, Coldplay and Shakira, Clark spends more time in Prevost coaches than in her own house.

For artists, moving from a minivan to a real tour bus is a game changer, not only for logistics but for the crew’s health and morale. A bus means no need to book hotels or eat out for every meal, since there’s a kitchenette onboard. Most importantly, each bus has a bathroom, and some even include showers.

On Beyoncé’s Cowboy Carter Tour, for example, that convenience is crucial, as she reportedly ordered around thirty Prevost buses.

Another reason the world’s biggest artists, as well as Formula 1 drivers, mobile banks in rural areas and even the U.S. president, choose Prevost is the near-infinite level of customization. “Justin Bieber even had a fireplace installed in his,” reveals Tremblay. While Prevost builds the vehicles themselves, several specialized companies handle interior conversions.

Each bus, made up of roughly 9,000 parts assembled over about 48 days, is then sent to a converter who tailors it to the client’s needs. Many amateur and professional sports teams also travel in Prevost coaches, while F1 drivers use their customized motorhomes as mobile headquarters.

Limitless Customization

Some artists opt for a full bedroom or a recording studio. As Clark tells me, the studio bus that followed Drake on his early tours was key to the creation of several of his biggest hits.

Other clients have more specific requirements, like Ground Force One, the code name for the two Prevost buses used by the U.S. president and the Secret Service. Equipped with ultra-secure communications systems and a range of classified features, they’re built on the X3-45 VIP model, the same type I saw being assembled that morning in Sainte-Claire. According to the Secret Service, Prevost was the only manufacturer with a chassis strong enough to support the extensive modifications and security systems required.

The Promise of Greener Touring

Today, the original factory site built by Eugène Prévost serves as a research and development center, ensuring the company continues to innovate. In the coming years, Tremblay says, the biggest challenge will be electrification. The first all-electric tour buses could be ready as soon as next year.“More and more artists are trying to reduce their carbon footprint. When you’re going from stadium to stadium, it’s actually pretty simple to plug in the bus and get ready to hit the road again, but of course, range is still the biggest challenge.”

As I leave the factory, a row of brand-new buses stands in the yard, lined up like spacecraft ready to launch into another world. Within days, they’ll be bound for Nashville, Rouyn-Noranda or Los Angeles, joining massive concert tours or professional sports convoys. It’s striking to think that from this village of just 3,000 people comes such a vital piece of North America’s entertainment infrastructure. Each bus assembled here carries not just Québec’s engineering expertise but also a distinct sense of craftsmanship, comfort and pride.

The models have changed, and so has the market, but the artisanal spirit imagined by Eugène Prévost still runs through every detail. The artists who sleep, write or celebrate aboard these buses may not realize it, but they’re living, quite literally, inside a small fragment of Québec.

Keep ReadingShow less

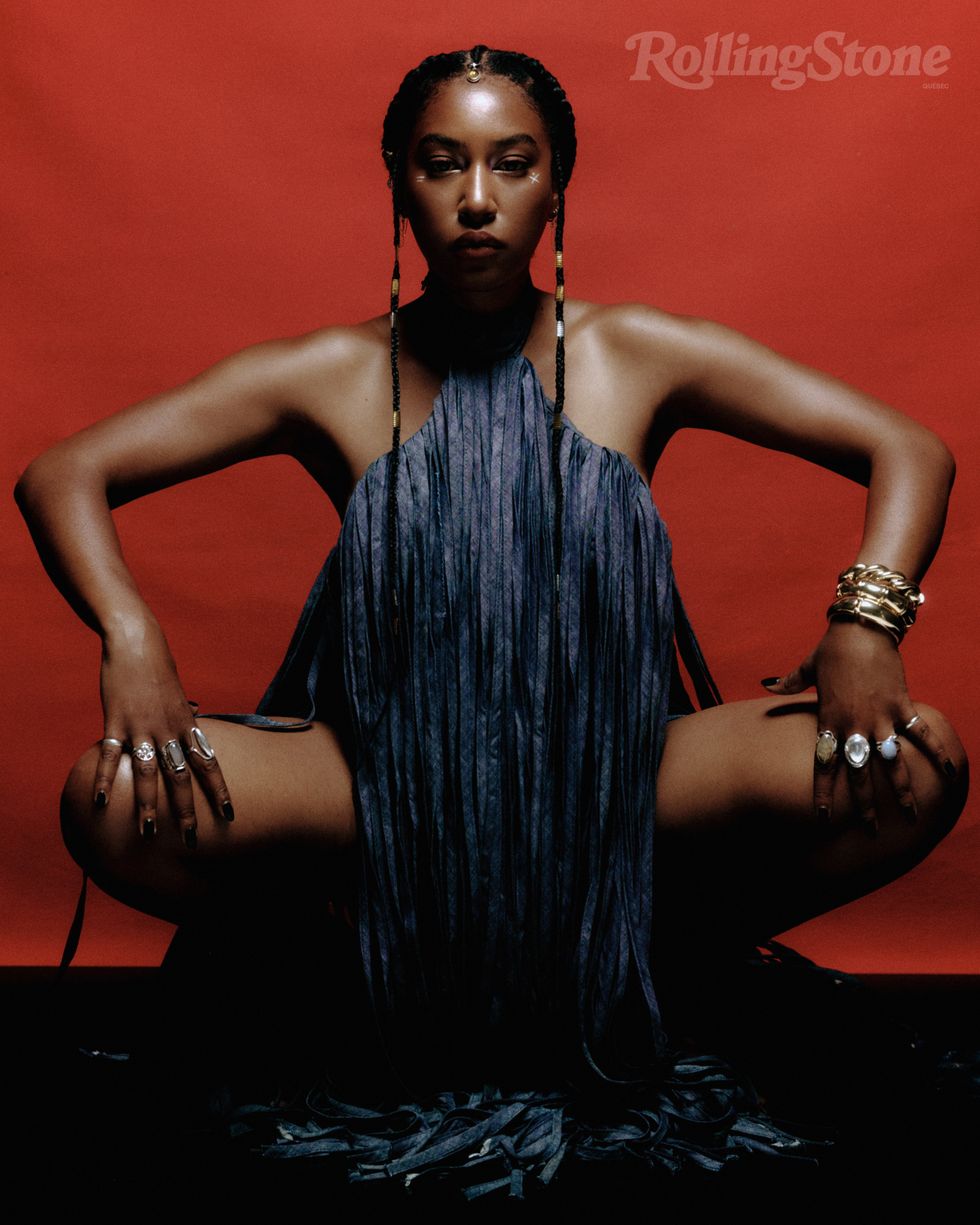

Rolling Stone Québec Future of Music 2025

Aug 08, 2025

Alexandra Stréliski

We could list a lot of impressive figures to showcase Alexandra Stréliski’s success: 600 million streams, 100,000 concert tickets sold, 10 Félix awards, 2 Polaris nominations, 1 Juno…

But the recognition the celebrated Québécois pianist enjoys stems more from intangible elements: the evocative power of her ethereal compositions, always infused with infinite gentleness; the beauty of her arrangements, which never fail to strike straight at the heart. Known for his discerning musical taste, the late filmmaker Jean-Marc Vallée, with whom Stréliski had developed a close friendship, included several of her melodies in his projects, from the series Big Little Lies and Sharp Objects to the films Dallas Buyers Club and Demolition, each time sparking strong emotions.

Beyond her creative work, Alexandra Stréliski also moves people through her sensitive, human, and humorous approach to life.

Though she currently describes herself as being in a “fallow period,” this well-earned break after two whirlwind years of touring will likely give rise to a new, rich, and promising creative cycle.

Alicia Moffet

Alicia Moffet’s highly publicized journey might give the illusion that we already know her.

She’s grown up in front of us for more than a decade, from her YouTube beginnings and appearances on shows like La Voix and Canada’s Next Star, to her influencer career and role as host on Occupation Double. But her latest album, No, I’m Not Crying, reminds us there’s still much to discover when it comes to her music.

With this third record, and her first on Cult Nation (Charlotte Cardin, Lubalin), the singer-songwriter leans into raw honesty and a clearly defined sonic direction.

Where her previous efforts, Billie Ave. and Intertwine, explored different balances between R&B and introspection, No, I’m Not Crying consolidates Moffet’s sound, blending emotional alt-rock with accessible yet uncompromising pop. The track Choke, which went viral in the spring, captures this approach: instantly catchy, with sharp lyrics and a powerful contrast between the vulnerability in her voice and the roaring guitars.

Fredz

He looks the part, some might say. Round glasses, bowl cut, soft voice — Fredz looks more like a teacher’s pet than a massively popular rapper.

But behind that discreet appearance lies one of the most distinctive voices in Québec’s emerging scene.

Originally from Longueuil, Frédéric Carrier wrote his first lyrics as a teenager, learned guitar through YouTube, and built a hybrid universe where cloud pop meets melancholic rap, framed by lyrics that resonate strongly with Gen Z.

- YouTube www.youtube.com

His latest album, Demain il fera beau, confirms his status as a unique singer-songwriter. While he shares some traits with introspective rap traditions, Fredz stands out for the way he draws listeners into his world. With a sober but polished aesthetic, he constructs a cohesive universe where each track has its own mood. On stage, he draws a devoted, multigenerational audience on both sides of the Atlantic.In a music landscape filled with clichés and hype, Fredz opts for nuance, softness, and attention to detail. A different way to approach rap: grounded in the real world, and bound to inspire many more in the years to come.

Laraw

With a pop sound that swings from soft to punchy, Laraw defies expectations.

A Montréal-based artist of Moroccan and Lebanese descent, she’s been making her mark on the local scene for several years now. Her online presence, radio play, and festival appearances have only grown since the release of Quarter Life Crisis in 2024. But behind the image of an accessible pop singer lies a songwriter with a dense and nuanced world, constantly reinventing herself with every release.

Her latest track, Milk and Sugar, reinforces that impression. A bittersweet song about the early days of rekindled love, it features simple yet incisive lyrics, carried by an airy production co-signed by Tim Buron. This return to English after the EP J’ai quitté le Heartbreak Club confirms Laraw’s versatility, equally at ease with the codes of francophone songwriting and global alt-pop.

In a Québec music landscape increasingly open to atypical and ambitious projects, Laraw represents a new generation capable of speaking to multiple audiences at once. She stands out for her consistent creative vision, unapologetic vulnerability, and her ability to turn doubt into infectious hooks.

High Klassified

At first glance, High Klassified might seem to exist outside the local scene.

A Laval-born beatmaker who came up through Fool’s Gold Records, he’s produced for artists like Future, The Weeknd, Hamza, and Damso, before circling back to lay the foundations of a more personal project. But behind the international aura, Kevin Vincent remains a creator deeply rooted in his suburban home turf, which he both celebrates and transforms in his own way.

With Ravaru, his latest album, he takes on a challenge few producers dare attempt: building a cohesive narrative universe where futuristic textures, R&B melodies, vaporous funk, and Japanese animation influences coexist. Ravaru is “Laval” pronounced with a Japanese accent: a way to reimagine his hometown like a video game, unlocking hidden treasures, shifting between light and darkness.

Rather than capitalize on his star-studded résumé, High Klassified chooses to double down on vision. He invites guests like Zach Zoya, Hubert Lenoir, Ateyaba, and Tsew the Kid — not to rack up features, but to serve a coherent, globally-minded body of work that remains true to himself.

Keep ReadingShow less

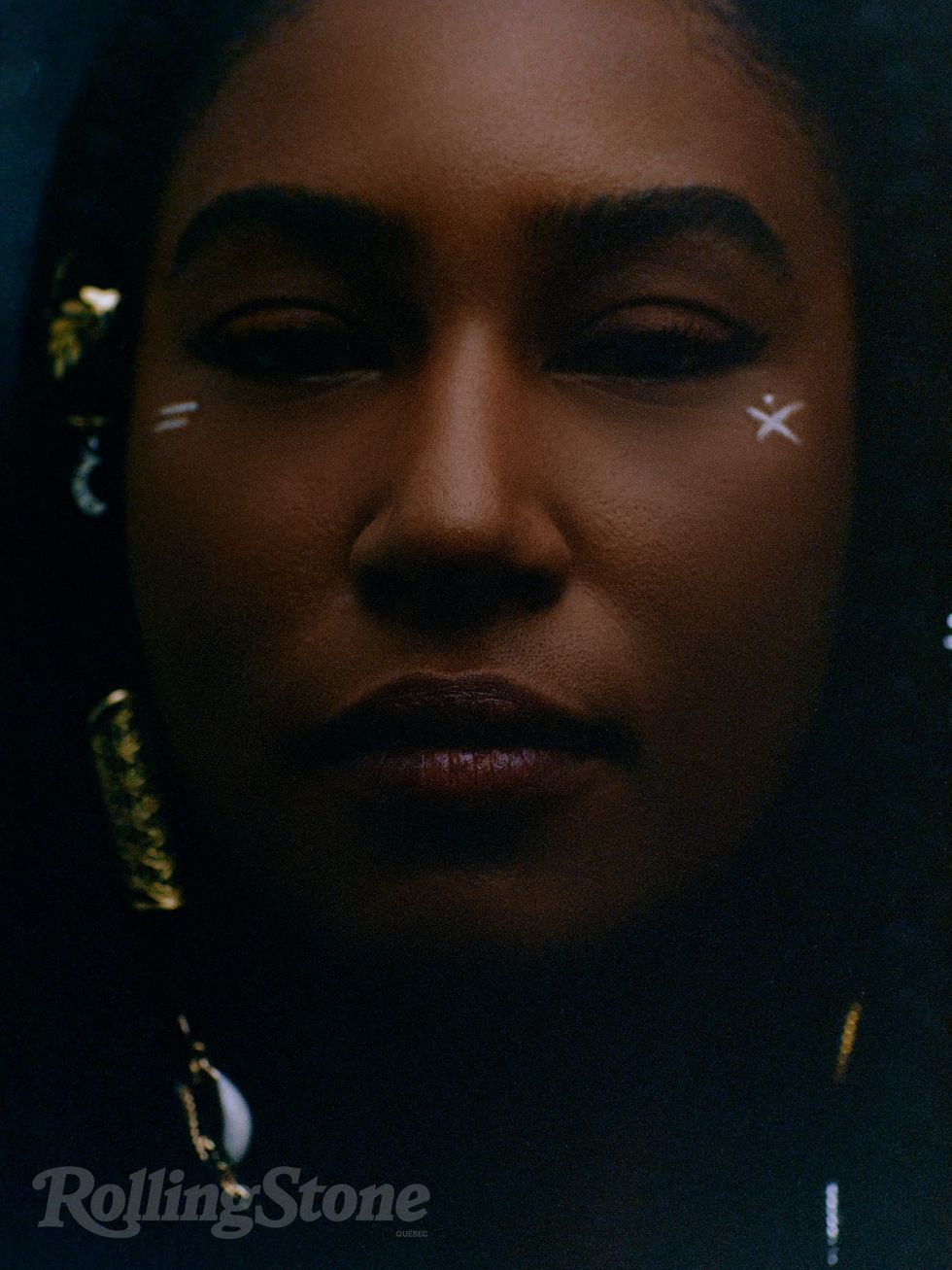

Kaftan: Rick Owens/Jewelry: Personal Collection & So Stylé

Photos by SACHA COHEN, assisted by JEREMY BOBROW. Styling by LEBAN OSMANI, assisted by BINTA and BERNIE GRACIEUSE. Hair by VERLINE SIVERNÉ. Makeup by CLAUDINE JOURDAIN. Produced by MALIK HINDS and MARIE-LISE ROUSSEAU

Dominique Fils-Aimé Follows Her Heart and Own Rules

Jul 04, 2025

You know that little inner voice whispering in your ear to be cautious about this, or to give more weight to that? Dominique Fils-Aimé always listens to it — especially when people push her to go against her gut instinct. The jazz artist doesn’t care for conventions or received wisdom. She treats every seed life drops along her path as an opportunity to follow her instincts. To go her own way. To listen to her heart. And it pays off.

The Montreal singer-songwriter tends to question everything we take for granted. Case in point: applause between songs at her shows. Anyone who’s seen her live knows she asks audiences to wait until the end of the performance to clap, so as not to break the spell she creates each time.

“I wanted to stop the usual format of ‘talk, sing, applause, talk, sing, applause.’ At first, people found it confronting. A lot of them said: ‘It makes me feel weird,’” she recalls. “But can’t we ask ourselves these kinds of questions more broadly in life? What are the little habits we’re so used to that not doing them makes us uncomfortable? Do they belong? What do they mean? We tell ourselves: ‘That’s the way it’s done, so let’s do it.’ Let’s question everything. Absolutely everything.”

Dominique Fils-Aimé questions absolutely everything, including the conventional music industry cycle — singles, then an album, then a tour. Even before releasing her debut album Nameless, she knew she wanted to make a trilogy. “I was often told people don’t have time for trilogies,” she says. “But I want to take my time. I want to invite people into a long-term process. I want to offer someone who’s curious the chance to go deeper into an artistic journey. Sure, it’s not for everyone, and that’s fine.”

I don’t want to be for everyone. I want to be myself.

This determination to follow her heart is the very essence of jazz — the genre she’s become a flagbearer for in Quebec. “Jazz is anti-academic. It’s about breaking down established rules. It’s the freedom to do what others say you can’t do. It’s a mindset. It's my mindset: creative freedom.”

In pure jazz tradition, Dominique Fils-Aimé recently released a live album documenting the major outdoor concert she gave last summer at the Montreal International Jazz Festival. A milestone in a remarkable career — recorded exactly ten years after the public first discovered her immense talent.

Asked what she remembers from that landmark show, she exhales with joy. “So many beautiful memories. Love, always. Waves of love. And deep gratitude to be on that stage.” Gratitude, especially, for the festival team — who, she recently learned, had been paving the way for this moment from the very beginning of her career.

“I was really lucky: the festival supported me from the start. At the beginning of my trilogy, my manager Kevin Annocque and I — who co-founded Ensoul Records — barely knew what we were doing. But I found out after last summer’s show that the festival team had everything mapped out from the first album, when I played the little room upstairs at MTELUS [the M2]. They had a whole long-term path planned to get me to the main stage!” she says, still in awe. “The lesson I took from that is: we worry too much about people talking behind our backs or sabotaging us, but we should really focus on the little angels along the way quietly conspiring for our success.”

One such angel is her sound engineer Simon Lévesque, whom she “loves dearly” and sees as a full-fledged member of her musical team. On his own initiative, he records every show in multitrack. “He sends us all the files. I don’t listen to any of them, but they’re there!” she laughs.

Of course, he recorded the Jazz Fest show — even though no one had planned to turn it into an album. Only afterward did Kevin Annocque convince her it was worth releasing. “He told me: ‘Hey, that was an amazing show! We should make it an album.’” At first, she wasn’t thrilled with the idea, thinking her vocals hadn’t been at their best. But she eventually changed her mind. “I realized that whatever the performance lacked in perfection, you can hear it in the emotion. And that’s worth keeping.” I tell her it was a great decision. “Yes, Kevin makes good calls!”

Indeed, he has good instincts. The singer’s warm, enveloping voice shines throughout the recording, from soaring peaks to hushed restraint. The energy of the show is palpable, magnified by 16 musicians and choristers on stage. From the a cappella opener—sung in monastic silence, a feat for Place des Festivals! — to the euphoric grooves of Grow Mama Grow, it’s a vibrant, joyful ride.

The set overflows with inspired improvisation, bold tonal shifts, and stunning vocal harmonies. It’s a perfect showcase of her musical journey so far, touching on jazz, soul, R&B, blues, gospel — even rock and hip-hop. For those who missed this ambitious concert, the album is pure joy.

The release comes amid a flurry of projects. Since January, barely a week goes by without a press release announcing a new venture — from performing at Expo 2025 in Osaka to Nikamotan MTL, a project bridging Indigenous and non-Indigenous artists — or news of an award, like those from the Dynastie Gala and SOCAN.

Last spring, she performed in Sweden, Germany, Spain, France, and England. In September, she’ll tour the U.S. for the first time. Meanwhile, between Quebec gigs — including Festif! in Baie-Saint-Paul and Théâtre de Verdure in Montreal — she’s recording her fifth album of original material in eight years.

Just summarizing her schedule is dizzying. For someone who claims to champion slowness, she’s impressively productive. She bursts out laughing when I point out the paradox. “Yes! Wow... One point for you, no one’s ever called that out before,” she says, genuinely surprised. “You’re 100% right. I’m passionate, maybe a bit extreme when I love something. I think I have an addictive personality. I got lucky it was music and not crack,” she jokes.

Even her production company, La Maison Fauve, noted that no other artist on their roster has released as many albums and tours without a break.

Ironically, it’s her commitment to the principles of slow living that makes her so productive, she argues. “Because I feel good. I could make music all day and not feel like I’m working. But I’m starting to realize — it is work. And I want to learn to slow down.” She’s thinking of taking a vacation in 2027 or 2028. “Might not be a bad idea, but...”

- Why stop when you’re inspired?

- Exactly. I’m having fun. I love what I do.”

Despite her packed agenda, she looks particularly serene and well-rested when we meet on a dreary May day at a Mile End café she frequents. In another life, she worked in corporate mental health and burned out. “I used to define myself through work. My job was my identity. That burnout made me let go and just follow where life was leading me.” Music became her lifeline.

To devote more time to it, she took a job at a café. That lifestyle fulfilled her completely, she says. Soon after, she met Kevin Annocque, who shared her vision of success. Together, they made a pact to create without compromise. “We decided not to make music just to sell. He told me: ‘We probably won’t be on the radio, we probably won’t make a lot of money, but if you’re okay with keeping a side job, I promise you’ll be free.’ That fit perfectly with my values. Others had tried to mold me, offering videos with backup dancers and saying I wouldn’t need to write — ‘we’ll give you covers.’ But I want to write! I want to create!” That’s why Dominique Fils-Aimé is so deeply grateful to now live off her art.

Dress: Helmer/Jewelry: Personal Collection

Though technically a solo act, she often speaks in terms of “we.” “I have the best team,” she says repeatedly during our conversation. “Honestly, there’s so much good music out there. The difference is the team,” she insists. She jokes that 90% of her success comes from her team, and only 10% from her talent. That seems modest. Too modest? “I’m just being realistic,” she says. “They deserve all the flowers.”

She repeats it after our photo shoot — four joyful hours with Sacha Cohen capturing her radiant presence. “It’s 90% the team, 10% talent!” she beams.

In her life and in her art, Dominique Fils-Aimé lives by three guiding principles: love, peace, and gratitude. She returns to these words again and again in our exchange — even though she says people have mocked those values as naïve. “In this world, I’ve been ridiculed,” she says. “You see it in people’s eyes — ‘you’re cute.’ Talking about love as a healing force or the power of universal love... people lump that in with hippie stuff.”

Her response? Follow her heart, always. “It’s not naïve. It’s not cheesy. It’s what we all want — peace and love. Why do they have such a bad reputation?”

When I suggest it might stem from cynicism, she lights up. “Yes! Exactly. There’s this idea of: ‘That’s all well and good, but it’s not the real world.’ But it is. It’s part of this world,” she says. “I can’t blame anyone for their views. I can only choose not to care — and hold to mine anyway.”

My deepest intention is to share love and good energy.

That’s the gentle resistance Dominique Fils-Aimé has been practicing from day one. Far from the superficial hashtagged “#gratitude” trend, hers is a deeper conviction — a form of soft power activism.

“I think revolution can take many forms,” says the 2022 Artist for Peace award winner, one of many accolades she treasures. “Some people are meant to speak out loudly, and I 100% support that. But there’s also backlash. I want to hold space where I can support those people — where I can promote the world I want to live in.”

That doesn’t mean she shies away from taking a stand. On April 5, in an Instagram post responding to global injustice, she wrote: “It's a strange place to be. Profoundly grateful for my life while deeply saddened by the state of the world… Fighting the useless guilt and despair with the hope my music brings love and light. It’s like trying to cultivate joy while mourning. Life is plural. Also, ‘defund the police’ means reinvesting in more adequate services. I'll just leave this here with a sigh.”

Her upcoming U.S. tour prompted deep reflection, especially considering Trump-era policies. But she reached a place of peace. “It’s possible to truly love everyone — even if I disagree with what they do,” she says. “If we shut out people who think differently, we deepen the divides. And that scares me. It’s made worse by online echo chambers — everyone’s in their own little bubble, and the other side seems far away and weird. I don’t want to fall into that trap. I don’t want to contribute to that divide. In the end, every person deserves love.”

It’s easy to forget now, but Dominique Fils-Aimé first appeared on the public radar through Quebec's adaptation of the The Voice —La Voix — in 2015. She joined simply to familiarize herself with the audition process and ended up a semifinalist. “I saw it as an experience. I love challenges. If something scares me, I have to do it. Because once it’s done, it feels so small. That’s always the case — our fears are bigger than reality,” she says with characteristic wisdom.

Three years later, she released Nameless, the first in her trilogy honoring the musical heritage of the African diaspora. A year later, Stay Tuned! brought her success and acclaim: a Juno for Best Vocal Jazz Album, a Félix for Jazz Album of the Year, a Polaris shortlist nod, and a spot as Radio-Canada’s Jazz Revelation.

She’s since released two more albums: Three Little Words, completing the trilogy, and Our Roots Run Deep, the start of a new creative cycle. Both earned Polaris nominations, and the latest also added more Junos and Félix trophies to her shelf. In recent months, she received SOCAN’s Hagood Hardy Award and the Dynastie Gala prize for International Artist of the Year.

How does she process all these accolades? They validate her place in music, she admits, but she tries not to focus on them too much. “It’s something I had to reflect on, because I don’t feel any competition with others. That goes against my values as an artist. I see everyone as my teammate. My well-being depends on my neighbor’s, and vice versa.”

That’s why she doesn’t keep her trophies at home. “My sweet mom has them all,” she says with a huge smile. “They’re on her mantel. She’s really proud. It warms my heart to give her that.” Like many immigrant families, hers — of Haitian origin — made sacrifices so their children could have better opportunities. “And I come from a family of scientists. My mom’s a doctor. I’ve always been surrounded by people with ‘serious careers’… These awards helped ease her worries when I chose music.”

People often say Dominique Fils-Aimé’s voice and music soothe the soul. But even in silence, she radiates kindness and warmth. Enough that I dare to briefly set aside my journalistic reserve and make a personal confession. I tell her how much her song Quiet Down the Voices, from Our Roots Run Deep, has helped me. Her eyes light up as she places her hands over her heart.

“Deep joy. Truly. Thank you for saying that. I created Quiet Down specifically to offer a space of calm for anyone who might need to recenter. If I need it, someone else surely does too!”

She hears stories like that all the time. “It fills me with gratitude when people take the time to share their experience. That’s worth 10,000 awards. I’ve always felt a mission to contribute to others’ well-being — but now I’ve found a way that nourishes me too. That’s heaven.”

Then she eagerly shares a song that gives her that same feeling: Sit Around the Fire by Jon Hopkins. “This song changed my life. It feels like a gift I was given, and now I want to share it with as many people as possible. I can’t wait for you to hear it!” she says, adding it to my phone.

Well-being, connection, the power of the present moment — that’s what Dominique Fils-Aimé explores in her second trilogy. Our Roots Run Deep is already about growth, our link to nature, and the interconnectedness of all living beings. She can’t reveal much about the next chapter, due in 2026, but she shares the mindset guiding her.

“I’m trying to embody this idea I often talk about: intentionality in music. Returning to childhood — creating for the joy of it, letting go of the thinking brain. I’m trying to stay as close as possible to raw emotion, to spontaneous truth. That’s pure jazz to me.”

Jazz says: it all sounds good. You are free.

She admits her pursuit of authenticity was once held back by modesty. “It took me three albums to say the word ‘love,’ even though it’s what I live and breathe all day long. It’s my favorite subject. That, and drinking water!”

After a long, timeless-feeling conversation in a noisy café, I turn off my recorder. Coat buttoned, umbrella in hand, Dominique Fils-Aimé hugs me and asks, with a smile, about my water intake. Clearly, she really does live on love and fresh water.

“Exactly! We’re like plants. That’s all we really need.”

Keep ReadingShow less

Cotton two-piece by Marni, SSENSE.com / Shirt from personal collection

Photographer Guillaume Boucher / Stylist Florence O. Durand / HMUA: Raphaël Gagnon / Producers: Malik Hinds & Billy Eff / Studio: Allô Studio

Pierre Lapointe, Grand duke of broken souls

Feb 14, 2025

Many years ago, while studying theatrical performance at Cégep de Saint-Hyacinthe, Pierre Lapointe was given a peculiar exercise by his teacher. The students were asked to walk from one end of the classroom to the other while observing their peers. Based solely on their gait, posture, and gaze, they had to assign each other certain qualities, a character, or even a profession.

Lapointe remembers being told that there was something princely about him. That was not exactly the term that this young, queer student, freshly emancipated from the Outaouais region and marked by a childhood tinged with near-chronic sadness, would have instinctively chosen for himself. Though he had been unaware of his own regal qualities, he has spent more than 20 years trying to shed this image, one he admits he may have subtly cultivated in his early days.

That, however, is proving to be a difficult task. With Dix chansons démodées pour ceux qui ont le cœur abîmé, his fifteenth full-length album, he once again asserts his boldness and classicism, solidifying his place as the Grand-duke of sensitive souls.

In 2004, Pierre Lapointe arrived ‘accidentally’, as he claims, onto the Quebec cultural scene with a grandiose and theatrical French Chanson, which starkly contrasted with the musical offerings of the time. Wedged between Crazy Frog, Gwen Stefani, and Simple Plan, a dandy who seemed to have been plucked from another century sang about his desire to lick every window of the columbarium, dreaming of sleeping there in peace, on a composition that sounded as if it had been borrowed from Jacques Brel himself.

Beneath Pierre Lapointe’s baroque elegance lies a mind in constant motion. From the moment his self-titled debut album found success, he never relented, continuously releasing albums, performing concerts, winning awards, and making television appearances.

But this frenzy came at a cost. Before the pandemic, the artist was pushing himself at a relentless pace.

"When everything stopped, I was heading straight into a wall. I was exhausted, I think I was on the verge of burnout. So, in a way, it was a blessing," he admits.

"My father used to ask me, whenever I talked about my schedule and how I felt, ‘But are you sleeping?’ And I’d answer, ‘Not much.’ That’s a sign that stress has taken over. He would tell me he was worried. When the pandemic hit, he was the first to say, ‘I’m glad you’re canceling everything and taking a break.’"

The timing of this break was perfect. When his longtime manager retired, Lapointe built a new team, leading to a shift in his approach, where he finally learned to do less. His new manager, Laurent Saulnier, the powerhouse behind the success of the Montreal Jazz Festival and Francofolies, gave him flak for being too prolific.

"He told me, ‘Your albums may be great, but you're saturating your own market. You release an album, and people don’t even realize it’s new. The messages are all getting mixed up.’"

For someone whose music is just one outlet for his creativity, this was a chance to return to other passions. After working on theater productions and film scores, Lapointe collaborated with Swiss visual artist Nicolas Party on L’Heure Mauve, an exhibition for which he created a soundtrack.

He also returned to drawing, having initially studied visual arts in Cégep, and designed various pieces of furniture, including a series of tables, carpets, and a Memphis-style lamp, "because the creator in me never stops." This forced break, he believes, allowed him to reconsider his approach to music and performance. He slowed down, rethought his creative process, and accepted that sometimes, less is more. Exploring other forms of art such as design, illustration, and scenography was not a diversion from music, but a complement that helps build his artistic universe. This multidisciplinary approach keeps his inspiration fresh without exhausting him. Having always envisioned his albums as total works of art, where visuals and music intertwine, Lapointe is now pushing that concept even further.

True to his love of theatricality, Lapointe has often structured his concerts as live tableaux. But the artist who once hid behind his piano now embraces a bolder, more embodied stage presence. For his upcoming show, he will stand front of stage almost the entire time, flanked by two pianists, Amélie Fortin and Marie-Christine Poirier, fully assuming his role as the central figure. This shift in stage presence stems from a broader reflection on his relationship with the audience, which has evolved over the years.

Early on, he explained that the piano acted as a shield between him and the audience, which adds another layer to ‘Toutes tes idoles’ when he sings: "You don’t like seeing people cry / It awakens the pain beneath / Of the child who grew up too fast and learned to arm himself to the teeth."

"Now, I want to be up front. I have no problem with it anymore, but back then, it was different. You have to understand that my teenage years were complicated," he confides. "I was deeply sad and depressed. I didn’t feel comfortable in my own skin, like so many teenagers. Being gay surely played a role in that. I found the world very ugly. I needed aesthetics, I needed beauty."

"Then the piano arrived. It lifted me up. It healed me. I would play notes, sometimes the same note for hours. And I would say, ‘I’m healing myself.’ The resonance calmed me. Looking back, it was a form of music therapy. I was healing through sound."

That healing process is especially evident on this album, particularly in the poignant “Comme les pigeons d’argile”, a tribute to his mother, written after her Alzheimer’s diagnosis. In “Madame Bonsoir”, he converses with the Grim Reaper, arriving, as always, at the worst possible time.

This album, however, was not originally intended for him. Lapointe explains that the songs in Dix chansons démodées pour ceux qui ont le cœur abîmé started as an exercise—an attempt to create something in the spirit of the classic French chanson he grew up with, but infused with his taste for the radical and refined. Initially, the plan was to offer these songs to other singers.

"There has never been an album where I went only halfway in a direction. When I finished writing these songs, which I had not written for myself, and then pieced them together, I realized I had to make an album out of them," he explains. "I told myself I had to go full speed ahead. The arrangements, my pronunciation—sometimes I pronounce the ‘E’ sounds like they did in the ’50s and ’60s Chanson réaliste [genre]. In the way I control my breath, in the fervor of my delivery, I went all in."

"Like Monique Leyrac, like Diane Dufresne, like Pauline Julien—artists who studied theatre, who ventured into Rive Gauche chanson [genre]. Singers who projected their voices like actresses, who could sing Kurt Weill as easily as they could sing Gilles Vigneault, but always with authority."

The Rive Gauche genre he evokes refers to the cultural movement that emerged in Paris’ left bank, in the 50s and 60s. In the heart of the Latin Quarter, intellectuals, artists and other bohemians would gather in smoky cabarets, where one could happen upon Sartre, Miles Davis, Juliette Gréco or Gainsbourg. Poetic, clamoring, theatrical; those are the songs that would come to redefine French music for the next half-century, and with which Lapointe grew up.

The result? Dix chansons démodées pour ceux qui ont le cœur abîmé has already become one of the most critically acclaimed albums of early 2025. At the time of publishing, it holds the top spot on the ADISQ sales charts.

January has been filled with constant back-and-forth travel between Québec, where Lapointe is preparing for his spring tour while also serving as the new coach on the TV series Star Académie, and France, where he has been spending several months a year.

He enjoys considerable success across the Atlantic, but more importantly, he holds the coveted status of an "Artiste"—with all the French reverence that title entails. Almost, as he jokingly puts it, as if he was more French than the French themselves.

Recently, after appearing on the hugely popular French television show Taratata, he was approached by the manager of a major French star, someone who had worked with all the greats of francophone music. "He told me that for years he had been trying to convince artists to make albums like they did in the era of Jacques Canetti, the 1960s music producer who discovered Félix Leclerc, among others. But every time, people backed out halfway, afraid to commit. He told me, ‘When I listened to your album, I felt like I was hearing a great record from that era, without compromise, yet completely contemporary.’"

Paradoxically, he also sees himself as the most Québecois of all Québec artists who have successfully exported themselves to France, when compared to figures like Garou, Isabelle Boulay, or Cœur de Pirate. "When I talk to people, they think I have a thick accent. To them, I’m unmistakably Québecois, with a very Québecois approach," says Lapointe. "(Those artists) are stars. Me, I’m a well-known singer in the Chanson world, and in a somewhat intellectual, outsider circle. The music industry, the contemporary art scene, the theatre world…"

It is true that his list of friends and collaborators is impressive. The music video for “Toutes tes idoles”, the first track on the new album, was filmed in the studio of ceramist Johan Creten. Lapointe was also invited to sing at the birthday celebration of French artist Jean-Michel Othoniel. On his Instagram feed, he is seen posing alongside the legendary Amanda Lear, Salvador Dalí’s muse.

"I have a strange status over there, one I don’t quite understand. I was named a Commander of Arts and Letters. Not a Knight—straight to Commander. I haven’t even received a medal in Québec or Canada yet!" he says, laughing. "I’m the only Canadian in history to have been immortalized by Pierre et Gilles, which is pretty funny. At the exhibition, there was Marilyn Manson and Madonna next to us. Nina Hagen was there too. And then there was Pierre Lapointe. Not Bryan Adams or Céline Dion."

There is a certain pride in his voice when he speaks about these experiences, but it is tempered by his naturally reserved nature. It is clear that Pierre Lapointe, despite his sharp pen and well-honed aesthetic sense, does not embody the role of an aloof, princely dandy. In fact, he struggles to understand how this perception took hold in the first place.

"When my success began, it completely overtook me, and my image was so strong that I could be walking down the street in sweatpants, and people would still call me ‘Sire’ and speak to me in poetic prose," he recalls. "I had only ever been to two or three poetry nights, and every time I just wanted to vomit on everyone and storm out yelling ‘You’re all so boring!’ And yet, here I was, suddenly considered a poet, with journalists asking me about Baudelaire and books I had never even read."

The dilemma in all of this is that it makes it even harder to pin down exactly who—or what—Pierre Lapointe really is. To strip him of the title of "poet" would be to overlook the raw and solemn beauty of a song like Le secret, which hides behind its bossa nova rhythms, and to forget the millions of tears shed around the world while listening to his music. And though he rejects the label of "dandy," he has nonetheless always been impeccably dressed at every one of our encounters, regardless of fatigue or illness.

The Pierre Lapointe we imagined on our television screens 20 years ago may not have been the one we thought he was. Or perhaps, he simply wasn’t that person yet.

Because despite all the sadness of his adolescence, and even though nothing was truly calculated, he feels that "there is a real symbiosis between who I knew I was and what I have done."

It was only last year, while promoting the 20th anniversary of his debut album, that he fully reconnected with the mindset he had back then. "It was as if I already knew everything that was coming," he recalls. "I knew I would work with individual artists, that I would be involved in theatre, that I would collaborate with directors, designers, architects. I knew I would travel, that I would make tons of albums, that I would go in all directions. But I hadn’t done any of it yet. When I talked to people, there was a gap between what I projected, what I said, and what I had actually done. Now, with hindsight, I understand."

In the end, perhaps Pierre Lapointe is not so much trying to escape his persona as he is trying to break free from a static image of himself—one defined by our perceptions rather than by the full scope of his talent or his desire to create something beautiful and meaningful.

By embracing, with pride, the role of the Rive Gauche crooner, he demonstrates that true audacity is not found in the medium itself, but in the sincerity of a fully and fearlessly realized artistic gesture.

Keep ReadingShow less

Load More

Rolling Stone Québec

ROLLING STONE QUÉBEC is a registered trademark of ROLLING STONE, LLC, a subsidiary of Penske Media

Corporation.

©2025 ROLLING STONE, LLC. Published under license.

©2025 ROLLING STONE, LLC. Published under license.